I’ve always been captivated by the grandeur of the German Imperial District of Strasbourg, a true embodiment of 19th-century German ambition.

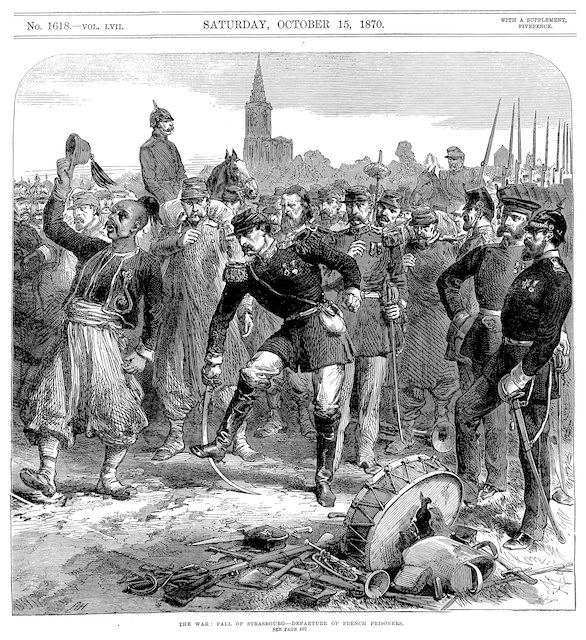

This iconic district was created in 1871 following the Treaty of Frankfurt, which redrew Europe’s borders and resulted in France ceding Alsace, Metz, and part of Lorraine to the expanding German Empire.

Strasbourg, annexed by Prussia, was meant to become much more than just another city; it was destined to symbolise the might of the new empire.

Positioned on the banks of the Rhine, between Basel and Frankfurt, Strasbourg was elevated to the status of capital of the Reichsland of Alsace-Lorraine.

In stark contrast to the picturesque old town on the Grande Île, the Neustadt (New Town) stands out with its imposing architecture, a testament to an era when every building was designed to impress and dominate.

So, let’s find out what makes this UNESCO World Heritage-listed district so unique and why it continues to fascinate visitors to this day.

The German Imperial District: A Historic Overview

From there, the German empire decided to develop a new city (“Neustadt”) beyond the perimeters of the old island town.

This planned extension responded to two major issues:

- to attend to the growing need for housing in the new regional capital (many German civil servants were moving to Strasbourg),

- and to create a showcase of German skills in the fields of urban planning and architecture.

This also allowed the German authorities to gain the confidence of the local population, which had been French for two centuries.

As such, several monumental constructions were built there: the library and the University Palace, the train station, the post office, Parliament House…

The urban planning by Conrath

Architect Conrath worked on urban planning, allowing the city’s surface area to be tripped to absorb the influx of German immigrants.

The district was irrigated by broad, straight, often tree-lined avenues, influenced by the Haussmann urban planning in Paris.

From 1871 to 1914, the city’s population doubled, industries rapidly developed, and intellectual activity intensified.

This exemplary operation of the “new city” is not unlike the similar one implemented in Metz by the German emperor.

![Strasbourg Neustadt Map. Image by Niko67000 - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Strasbourg-Neustadt-Map.-Image-by-Niko67000-licence-CC-BY-SA-4.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.png)

The Francisation of the Neustadt of Strasbourg

Today, the names of places, boulevards, avenues and palaces share the republican-sounding French names: Avenue de la République, Avenue de la Marseillaise or de la Liberté, Boulevard de la Victoire…

However, at the time of their creation, they had very German names to the glory of the German homeland.

In the early 1880s, the architectural style of the buildings was eclectic.

The trend combined many architectural styles: Roman, Gothic, Renaissance, Classical and Baroque.

With the rise in power of Art Nouveau in Europe, the style of the new buildings took on Jugendstil, its Germanic version, characterised by the abundant use of floral motifs.

Strasbourgeois architect Geoffroy Conrath‘s planning was handed in in 1879, and the works included prestigious buildings representative of the power around the Imperial Palace (Kaiserplatz) and many public buildings that would become iconic in the city.

The main sights of Strasbourg’s German Imperial District

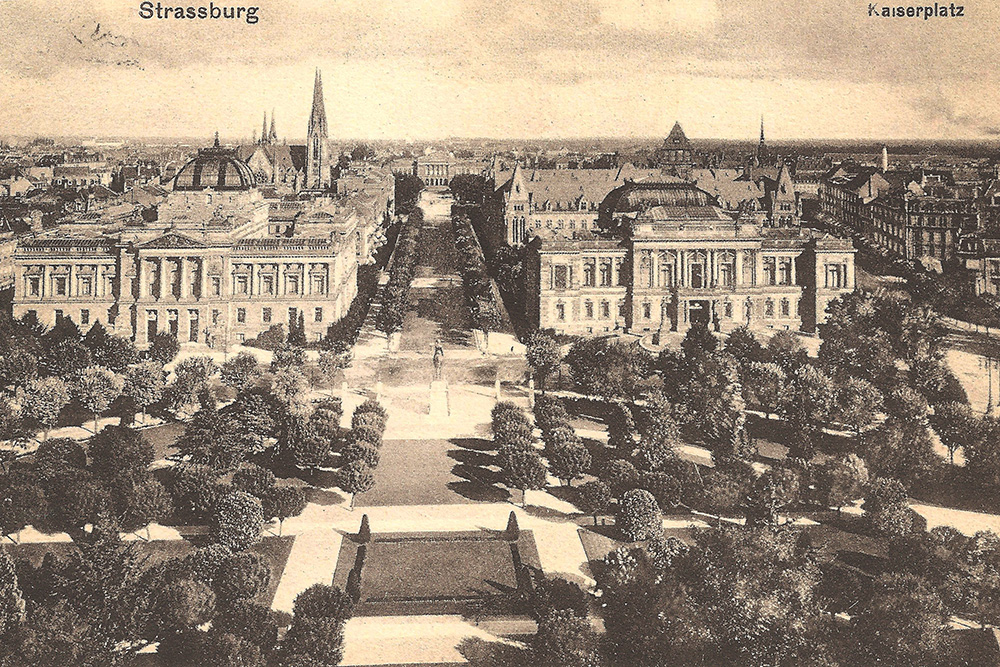

La Place de la République

Kaiserplatz

This vast public garden, with a large square in its centre, is bordered by prestigious buildings that are considered among the most beautiful of Wilhelmian architecture.

In the middle of magnolia trees, at the centre of the gardens, stands the poignant war memorial, sculpted by Drivier in 1936.

It represents a mother (Alsace) holding her children killed in combat—one who died for France, the other for Germany.

Le Palais du Rhin

Kaiserpalast, The Emperor’s Palace, now “Palace of the Rhine”.

Majestically bordering Place de la République, this is certainly the most emblematic building in the “Neustadt” with its imposing dome.

It was built between 1883 and 1888 in a Neo-Renaissance style by Hermann Eggert, who wanted to showcase the definitive establishment of the German presence in Strasbourg.

Upon seeing it, Emperor William I had only one reaction: “Gigantic!”

The emperor did not have time to stay there; he died shortly before the building’s completion.

Thus, his grandson, William II, made it his official residence during his stay in Strasbourg. William II came here more than a dozen times until 1914.

Today, the Palace is home to the Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine and the Regional Direction of Cultural Affairs (RDCA).

Le Théâtre National de Strasbourg

Landesausschuss, the Building of the Delegation of Empire Territory, now “National Theatre of Strasbourg”.

![Théâtre National de Strasbourg. Photo © Ralph Hammann - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Theatre-National-de-Strasbourg.-Photo-©-Ralph-Hammann-licence-CC-BY-SA-4.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

It was built between 1888 and 1899 in a Neo-Classical style to accommodate the Delegation of Empire Territory.

This gathering has a consultative function for the budget and legislation (which were voted on in Berlin).

It became the Parliament for the Reichsland of Alsace-Lorraine in 1911.

After the First World War, it housed Strasbourg’s Conservatory of Music.

Linked to the Ministry of Culture since 1972, it is the first national theatre established in Provincial France.

La Bibliothèque Universitaire

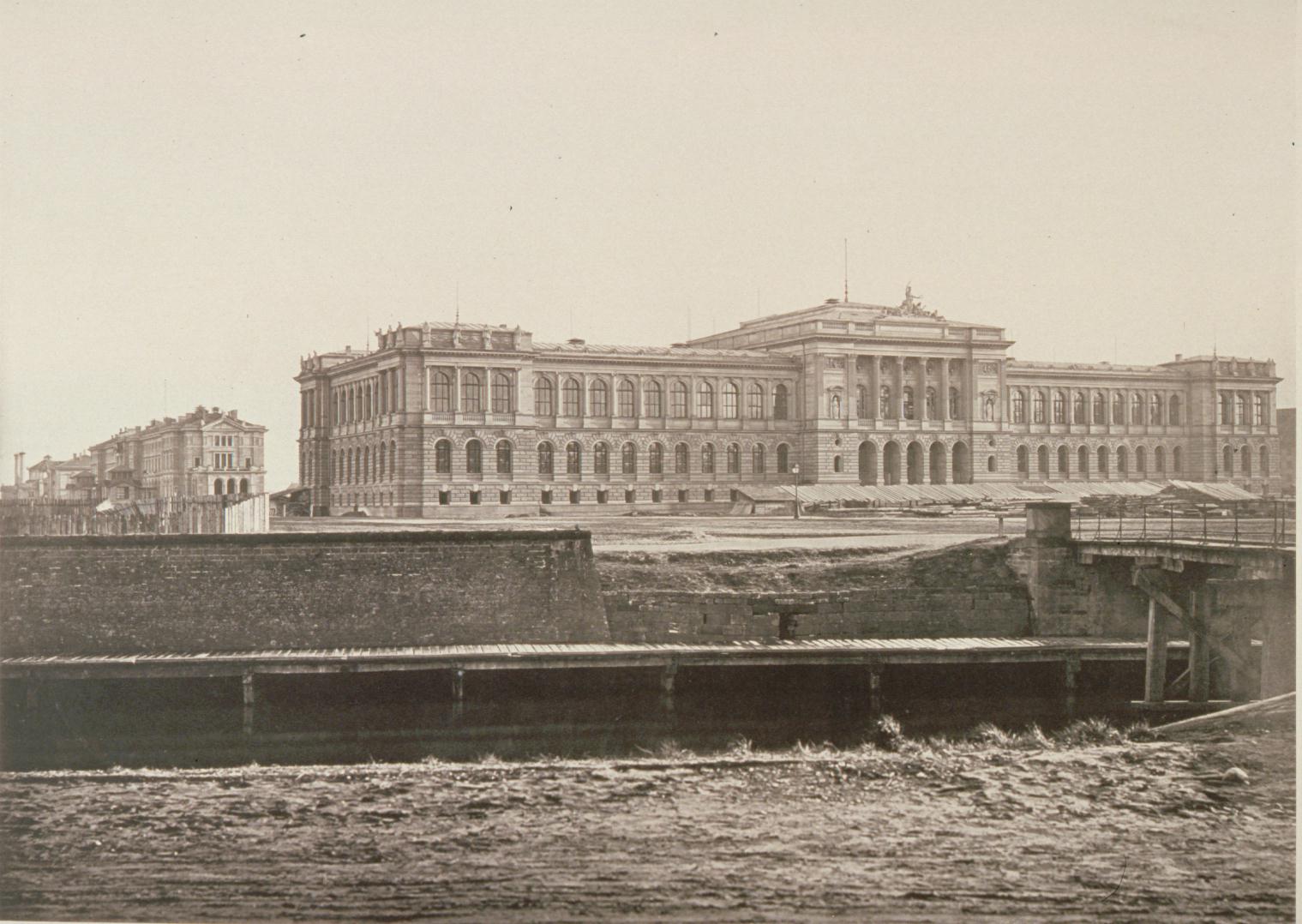

Kaiserliche Universitäts und Landesbibliothek zu Strassburg, the University Library, also called BNUS.

![Bibliothèque Universitaire de Strasbourg. Photo by Claude Truong-Ngoc - licence [CC BY-SA 3.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Bibliotheque-Universitaire-de-Strasbourg.-Photo-by-Claude-Truong-Ngoc-licence-CC-BY-SA-3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

The prestigious Italian Neo-Renaissance style building officially incorporated the imperial library on the 29th of November 1895.

Strasbourg’s library was entrusted with library works (that would later be destroyed by the bombings of the Second World War) from several German libraries: Königsberg (40,000 precious copies), Göttingen, Munich, Dresden, Heilbronn or even Schweinfurt.

Emperor William I himself offered 4,000 volumes from his collection.

In 1875, the donor count was at 2,750, and in 1879, the library contained 386,073 books, becoming the fourth-largest library in Germany.

At the dawn of the Second World War, most collections were moved to various storage areas in Alsace and around Clermont-Ferrand (Auvergne).

The library’s collections are estimated at more than 3 million documents, many of which were written in German, an exceptional finding in France.

Along with Lyon’s, it is among the most prominent libraries outside Paris.

Le Palais Universitaire

Kaiser-Wilhelms-Universität Strassburg, the University Palace.

![Palais Universitaire Strasbourg. Photo by Jonathan Martz - licence [CC BY-SA 3.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Palais-Universitaire-Strasbourg.-Photo-by-Jonathan-Martz-licence-CC-BY-SA-3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

Of all the buildings erected in 1884 by Otto Warth (an architect from Karlsruhe), the University Palace is the most harmonious.

It grandly closes the beautiful view of the Avenue de la Liberté from the Palace of the Rhine.

Its façade, made of yellow sandstone and inspired by Genovese palaces of the Italian Renaissance, is punctuated by columns and statues of great men (Kant, Leibniz) and features a wide staircase entrance.

The influence of the University of Strasbourg in Germany attracted many eminent professors within its walls.

The Palace today still caters to some academic fields (history and art history).

Le Temple Saint-Paul

Paulskirche, the Lutheran church of St. Paul

The church stands on a headland of the Ill River divided in two at the side of the University Bridge.

The Neo-Gothic building was created between 1889 and 1897 by architect Luis Müller, inspired by the St. Elizabeth Church in Marburg (Germany).

Like a Gothic cathedral, the church dominates the imperial district with its two twin spires reaching 76 metres.

Its nave can accommodate almost 3,000 worshippers.

It was designed for the Protestant German garrison stationed in Strasbourg between 1871 and the Great War.

Since 1918, the church has been dedicated to the Reformed Protestant religion.

La Gare Centrale

Strassburger Bahnhof, the Railway Station.

Much like the railway station in Metz, Strasbourg’s Railway Station was erected by German authorities and served the military interests of the Second Reich.

It was decided to build it on the virgin land of the former Vauban Fortifications.

Inaugurated in 1883, the station by Berlin architect Johann Eduard Jacobsthal was an essential step for the great international axis of Paris-Vienna and Basle-Cologne.

Its proportions were gigantic for its time: a 128-metre-long façade inspired (loosely) by the Renaissance, with two storeys (the ground floor is located on the wide semicircular area—and the upper floor at the level of the platforms), a welcome hall and arrival hall, and 300-metre-long platforms.

Two stained glass windows, one celebrating the glory of Germany and the other celebrating the union of Alsace to the Empire (Frederick Barbarossa in Haguenau and William I in Strasbourg), decorated the central hall until 1918.

The railway station recently underwent significant renovations, given the arrival of the TGV Est Européen in June 2007.

Particularly, a vast glass roof covering the whole of the façade was installed.

Since the high-speed line between Strasbourg and Lorraine opened in 2020, Paris is no more than 1 hour and 50 minutes from the Alsatian capital.

A UNESCO listing of Strasbourg’s German Imperial District?

In January 2016, the City of Strasbourg and the Ministry of Culture applied to extend the UNESCO World Heritage site to include part of the Neustadt.

The application is entitled “From the Grande-Île to the Neustadt”.

Then, on July 9, 2017, the UNESCO ambassadors decided to respond positively to the application by registering the central part of Neustadt as a World Heritage Site.

The perimeter selected for the extension extends from the courthouse area to Arnold Square.

It includes the Imperial axis linking the Place de la République to the university, the Avenue des Vosges, and the Avenue de la Forêt-Noire.

![Strasbourg German Imperial District. Photo by Zairon - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Strasbourg-Kaiserplatz.-Photo-by-Zairon-licence-CC-BY-SA-4.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

Learn more about the Neustadt of Strasbourg

- Discover our pages on Strasbourg.

- Read more about the German imperial district of Strasbourg (or Neustadt) on Wikipedia.

- Learn more about Strasbourg on our French blog Mon Grand-Est.