The famous Place Vendôme in Paris’ First arrondissement ranks amongst France’s most beautiful squares. Located to the north of the Tuileries Garden, it is a magnificent example of neoclassical architecture in France, similar to the squares of Place de la Concorde (Paris), Place de la Bourse (Bordeaux) and Place Stanislas (Nancy).

A mecca of money and luxury, Place Vendôme provides a base for renowned and prestigious establishments: the Ritz hotel, Cartier, Rolex, Chanel jewellery, as well as the Ministry of Justice; and in its centre the celebrated Column of Vendôme sits enthroned.

The upscale square is situated in the First Arrondissement of Paris between the Tuileries Garden and the Opéra Garnier.

History of Place Vendôme

The design of the square was entrusted to Jules Hardouin-Mansart. Respecting the constraints of a rigorous town-planning formula, he designed the square in 1699 with its façades listed as historic monuments.

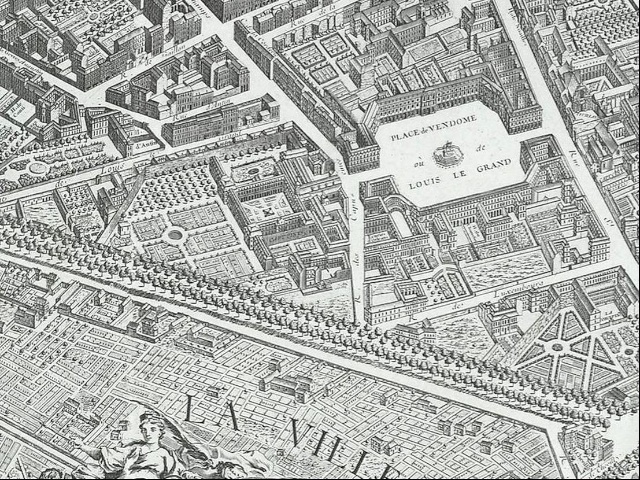

Initially named Place Louis le Grand in honour of Louis XIV, the square was later renamed Places des Piques after the French Revolution then Place Internationale in 1871 during the Second Commune of Paris. Today, the square takes its name from the former Hôtel de Vendôme which was located on the site.

The origins of the square from the 17th century to the Revolution

The project of laying out a square on the site of the ill-famed Convent of Capucines and the townhouse of the duke of Vendôme (illegitimate son of King Henri IV and Gabrielle d’Estrées) dates back to 1677. The townhouse was acquired by Louvois, superintendent for public buildings, in the name of the king, in 1685 with the intention of creating a square in which a monumental statue of Louis XIV would sit enthroned at its centre. Architects Jules Hardouin-Mansart and Germain Boffrand suggested a large rectangular square, which would be called “Place des Conquêtes” echoing the nearby “Place des Victoires”.

The façades of the square

Façades were erected before the actual buildings, which were intended to house prestigious institutions (royal library, mint house, academies hotel, and ambassadors’ hotel).

However, as a result of a slowing down due to over expenditure (the Treasury had already spent 2.3 million pounds) the works were never be completed and the King gave the land away for free to a private enterprise led by Jules Hardouin-Mansart. In return, the King required the conservation of the façades as the new project had to include townhouses with uniform façades. Louis XIV also wanted to scale down the initial dimensions of the square (initially 213 by 224 metres). Initially rectangular, it was altered by reducing two sides of the square by approximately 20 metres to create a square with cut-off corners.

The square dedicated to Louis XIV

A bronze equestrian statue of Louis XIV dressed as Caesar, sculpted by François Girardon, was set in the centre of the square in time for the 1699 inauguration.

In contrast to Place de la Concorde, this square (named Place Louis le Grand) is enclosed because it was designed on a North-South axis linking rue Saint-Honoré to rue des Capucines.

The architect did not create arcades on the ground floor because the building was intended to be residential.

The Mansart-style roofs were originally interspersed with alternating dormer and bull’s eye windows (the later would be mostly replaced by dormer windows in the 19th century).

The square taking shape in the 18th C

It took some time for the new square to take shape because the land behind the façades did not sell quickly. Between 1702 and 1720, the plots were sold on speculation by financiers, architects and independent customs agents. In 1718, the famous banker John Law bought almost half of the square before becoming bankrupt two years later. (He narrowly escaped a lynching of stockjobbers on the same square).

But it was the architect Hardouin-Mansart himself who benefited from this business when in 1703, he acquired the three best plots in the square (numbers 7, 9 and 11). Plot 11 became the Royal Chancellery (today the Ministry of Justice) from 1717.

The Place des Piques during the Revolution

As much as the Louvre symbolised monarchist power, so did Place Louis le Grand, with its town houses, reflect privilege. It is therefore not surprising that the Revolutionaries were drawn to this symbolic site.

The Place Louis le Grand suffered the consequences of the Revolution during the year 1792.

On August 8, 1792, a group of women led by Théroigne de Méricourt slaughtered nine royalist prisoners before parading their heads on top of spears. Following this event, the Place Louis le Grand was renamed Place des Piques and would keep that name until 1799.

On 10 August, Danton orchestrated the fall of the monarchy and the following day besieged the Royal Chancellery in order to set up the temporary government of the new Republic there. Appointed as Minister of Justice and head of the temporary government, it was in the same building on the square that he planned the battle of Valmy where French soldiers won victory over the Prussian and Austrian armies.

Collateral death…

The illustrious equestrian statue of Louis XIV, sculpted in 1692, was removed on 13 August 1792. Its fall led to the death of Reine Violet, a news vendor of Marat’s newspaper “l’Ami du Peuple”. In order to bring down the statue, she threw a rope over it. Ignorant that the bolts from the bronze horse and Louis XIV had been removed previously, the news vendor, suspended to the rope, ended up being squashed by the falling statue. The only remnant of the statue is exhibited in the Carnavalet Museum (4th arrondissement): it is the bronze foot of the king, weighing 150 kgs.

The “mètre étalon”

Notice to the left of the ministry’s gate the marble sign “mètre étalon” affixed in 1796 and 1797 (and replaced in 1848) for Parisians to get familiar with the new measurement unit. It was part of a set of 16 mètres-étalon dispatched in the French capital and of which only four survive today (the other three are located at 36 rue de Vaugirard, in Croissy-sur-Seine (Yvelines) and in Sceaux (Hauts-de-Seine). The base unit of length of the International System of Units was officially defined for the first time on March 26, 1791 by the Académie des sciences.

The Death of Saint-Fargeau

On the night of the 20th January 1793, Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau (who had just voted for the death penalty for King Louis XVI) was stabbed to death with a sword at the Palais-Royal by a former bodyguard of the King. Transported to his brother’s home at Place Vendôme, he died the following day a few hours before the King’s execution. Painter Jacques-Louis David was asked to exhibit his body on a grandiose stage on Place Vendôme. His body was placed on a plinth in the centre of the square. Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau was considered the first martyr of the French Revolution.

After the Revolution

On 19 February 1806 it was decreed that rue Napoléon (today known as rue de la Paix) would be cut in between Place Vendôme and boulevard des Capucines, authorising the de facto destruction of the Capucines convent. The decree was intended to create Paris’ most beautiful street and also included a requirement that a monumental column be raised in the centre of the square following the model of Trajan’s Column in Rome. The Paris column was to be built from the bronze of the canons confiscated during the battle of Austerlitz.

The rue de la Paix was completed under the reign of Louis-Philippe and became a prestigious stop off point for various foreign delegations on their way to the Tuileries Palace.

It was on this street that Marie-Antoine Carême (1784-1833) opened his first pâtisserie before cooking in most of Europe’s courts. But it was the urban redevelopment around the newly built Opéra Garnier by Baron Haussmann in 1861 that contributed to rue de la Paix and Place Vendôme becoming a mecca for the commerce of luxury.

The Vendôme Column

On the site of the equestrian statue of Louis XIV which sat enthroned at the centre of Place Vendôme, Napoleon installed the Vendôme column in 1810. This imitation of the Trajan Column in Rome was sculpted by Etienne Bergeret and was originally surmounted by a statue of Napoleon in Roman dress by Antoine-Denis Chaudet.

The erection of the monument reflected the ambitious Emperor who wished to pay homage to his victorious soldiers at the battle of Austerlitz.

Many names…

Since its edification, the column changed its name several times: Austerlitz column, then Victory column before being renamed Column of the Great Army (colonne de la Grande Armée).

Like in Rome, the Parisian column features a spiralling bas-relief: 425 plates of bronze have been sculpted from the drafts of Pierre Bergeret and depict the whole campaign of Austerlitz (1806), from the Boulogne Camp to the return of Napoleon and his victorious army to Paris on January 27, 1806. Put end to end, these plates reach a length of 220 metres!

The height of the bronze column is of 44.3 metres and its average diameter is 3.60 metres. It is believed that the column was covered with a bronze screed made of the 1,200 canons confiscated by the Russian and Austrian armies. However, historians believe that 130 canons at most were taken, the other number being very unlikely and more likely to be the Emperor’s propaganda.

The column is hollow as a stair which reaches a platform at the foot of the statue of the Emperor is constructed inside.

The base of the Vendôme column

The cubic base of the Vendôme column is made of granite from Corsica and the bronze bas-reliefs depict a pile of trophies, canons, weapons, flags and uniforms of the Austrian army. The entrance door is topped by two Renommées which support a bronze plate whose Latin dedicatory inscription refers to the 1806 Napoleonic campaign:

NEAPOLIO IMP AVG

MONVMENTVM BELLI GERMANICI

ANNO MDCCCV

TRIMESTRI SPATIO DVCTV SVO PROFLIGATI

EX AERE CAPTO

GLORIAE EXERCITVS MAXIMI DICAVIT

“Napoleon, august Emperor, dedicated to the glory of the Great Army this column, monument made of bronze conquered over the enemy during the war of Germany in 1805, war which, under his commandment, was completed within three months”.

Who’s at the top of the column?

At each change of political regime, the statue which sits on top of the column was replaced by another one. Thus, the first statue of Napoleon depicted him dressed as a Roman emperor, holding in his left hand the terrestrial globe topped with a winged-Victory. This statue was briefly replaced by that of King Henri IV on April 3rd 1814 and then, under the reign of Louis XVIII by a fleur-de-lis.

On 28th July 1833, under the July Monarchy, the top of the column hosted a statue depicting Napoleon as “Petit Caporal” (dressed with a frock-coat and wearing a cocked-hat), sculpted by Charles Emile Seurre. On 4th November 1863, by order of Napoleon III, a statue similar to the first one, with Napoleon dressed as Caesar and wearing a laurel wreath, found its way to the top of the column. The former statue of Napoleon as “Petit Caporal” was transferred to the main courtyard of the Hôtel des Invalides where it still stands today.

The column knocked down during the Paris Commune!

As for the column, it was knocked down on May 16, 1871 by Gustave Courbet, in charge of all the Paris art museums during the Paris Commune. The French painter was sentenced to rebuild the monument in identical formand and at his own expense.

However, even though Courbet managed to negotiate spreading the payment of 10,000 francs per year over 33 years, he died before having paid the first instalment.

The column underwent restoration work under the patronage of the Ritz Hotel in 2015.

In the same style of monument, we can mention the July Column in the centre of Place de la Bastille and the Column of the Great Army in Wimille, near Boulogne-sur-Mer.

Place Vendôme and its townhouses

Place Vendôme is almost a perfect square 213 m by 224 m and all its townhouses are unified with their façades punctuated by monumental Corinthian pilasters which link the storeys thus giving them a majestic scale worthy of a palace. Despite this rigorous structure, monotony is avoided thanks to the pavilions built on the façades which compliment each other, and to the angles of the square which are softened by cut-off corners.

More than twenty townhouses, full of history, border the square. Some have gained an historic reputation:

The Bataille de Francès hôtel (number 1).

This townhouse dates back to 1723 and was built for Pierre Perrin, the King’s secretary. After housing the Bristol Hotel (where Edward VII, the king of England stayed), it became the Vendôme Hotel.

The Bourvallais hôtel (number 13)

The seat of the Ministry of Justice. It was built in 1699 for Joseph Guillaume de La Vieuville. Bought back in 1706 by the financier Paul Poisson de Bourvaillais, it became the headquarters of the Chancellery following the combination of the building with number 11.

The Gramont hôtel (number 15)

It houses the celebrated Ritz hotel, one of Paris’ grandest palaces. It owes its name to Duke Antoine Charles IV of Gramont who married the maid of a doctor of Louis XIV. In 1714, financier John Law lived in the townhouse and in 1721 the Duchess of Gramont, recently widowed, sold it to Daniel François de Gelas de Voisin (1686-1762), knight of Ambre and count of Lautrec. It is from the window of the salon of this townhouse that the young Louis XV in 1721 attended incognito the magnificent procession of the Ambassador of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1898, the building was transformed into a traveller’s hotel by César Ritz. Today, the establishment belongs to Egyptian billionaire Mohamed Al-Fayed. The hotel made the headlines on the night of the 31st August 1997 when his son Dodi and Princess Lady Diana left from here before dying in the Alma Tunnel.

The Heuzé de Vologer hôtel (number 4)

It takes its name from Geoffroy Chalut de Vérin, farmer-general who bought a one third share with his wife Elisabeth de Varanchan in 1751.

Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who would later be known as Napoleon III, resided in the townhouse in 1848 when he was President of the Republic.

The Baudard de Saint-James hôtel (number 12)

Acquired in 1699 by financiers Herlaut and Besnier, in 1700 the property was passed to Louis Dublineau, Prior of Longchamp, who built the current townhouse.

Later in 1777, the building was bought by Claude Bardard de Saint-James, creator of the Folie Saint-James in Neuilly-sur-Seine. It hosted the Russian Embassy and it was on the first floor that composer Frédéric Chopin died from tuberculosis in 1849. Napoleon III met his future wife, Countess Manuela de Montijo, later Empress Eugénie there. Today, the building houses the Chaumet jeweller.

Place Vendôme: so much luxury in a same place!

Considered by the French as the world centre of jewellery, Place Vendôme hosts some of the most celebrated names: Boucheron, Chaumet, Mauboussin, Cartier, Van Cleef and Arpels. The area around the square (rue de la Paix, rue Saint Honoré and rue de Castiglione) abounds in perfumeries, goldsmiths, crystals stores, banks, fashion houses, not to forget the mythic Ritz, one of the first Parisian palaces noted for having been visited by Proust and Lady Di.

The restoration of the square in 1992 contributed to Place Vendôme becoming a tourist hotspot, a jewel wonderfully highlighted as soon as night falls thanks to skilful lightning.

Place Vendôme: a homage to the city of Vendôme

What is the link between Place Vendôme and the city of Vendôme in the Loir-et-Cher département?

The answer lies in history, to the origins of the square when the current site was occupied by the townhouse of the Duke of Vendôme.

The Duchy of Vendôme (and before it the County of Vendôme) belonged to a branch of the royal family: the Bourbon-Vendômes.

Today, the traditional limits of the Duchy correspond more or less to the Vendômois Region, comprising the constituency of Vendôme to the North of the department of the Loir-et-Cher (head city: Blois), spreading on each side of the Loir River (not to be confounded with the Loire!)

Thank you very much for this beautyful and profound choice of contents.