This research on the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace tells how a peace treaty signed in 1648 not only ended the Thirty Years’ War, but also changed the fate of a region caught between empires.

Signed in October 1648, the Treaties of Westphalia brought an end to one of the most devastating wars Europe had ever known — the Thirty Years’ War.

By the mid-seventeenth century, the continent was exhausted.

The countryside lay in ruins, cities were destroyed, and populations decimated.

What had begun as a religious conflict between Catholic and Protestant princes within the Holy Roman Empire had turned into a struggle for power, in which France, Sweden, Spain and the Habsburgs competed for supremacy across Europe.

To halt this spiral of destruction, the great powers gathered in two Westphalian towns — Münster and Osnabrück — and in October 1648 signed a series of historic agreements: the Peace of Westphalia.

Ratification of the Peace of Westphalia, 1648 – painting by Gerard ter Borch

These treaties did more than restore peace.

They laid the foundations of the modern world, built on state sovereignty and multilateral diplomacy.

Yet beyond their continental impact, the treaties had deep and lasting consequences for one particular region: Alsace.

For it was here — in this borderland between the Germanic and Latin worlds — that the peace of 1648 brought about one of the greatest political transformations in French history.

The Treaties of Westphalia did not merely redraw a map; they upended an old order, ending centuries of Habsburg domination and initiating the gradual integration of the province into the Kingdom of France.

This transition, however, did not happen overnight.

Between 1648 and the end of the seventeenth century, Alsace evolved from a patchwork of lordships, free cities and abbeys into a fully-fledged French province — though one with a singular status, shaped by remnants of Imperial law and a profound cultural duality.

France did not conquer Alsace by force; it absorbed it through law, diplomacy, and a carefully crafted strategy of ambiguity.

In the following pages, we’ll retrace this fascinating evolution —

how the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace transformed a political mosaic into a French province, through the legal, administrative and cultural steps of a process that spanned more than a century.

Alsace Before the Peace of Westphalia: An Imperial Mosaic

Before 1648, Alsace was far from a unified province.

Lying on the left bank of the Rhine, it belonged to the Holy Roman Empire and was one of its most fragmented territories.

The phrase “imperial mosaic” perfectly describes the region’s complexity — a patchwork of lordships, abbeys, free cities, bishoprics and princely domains, each fiercely protective of its rights and privileges.

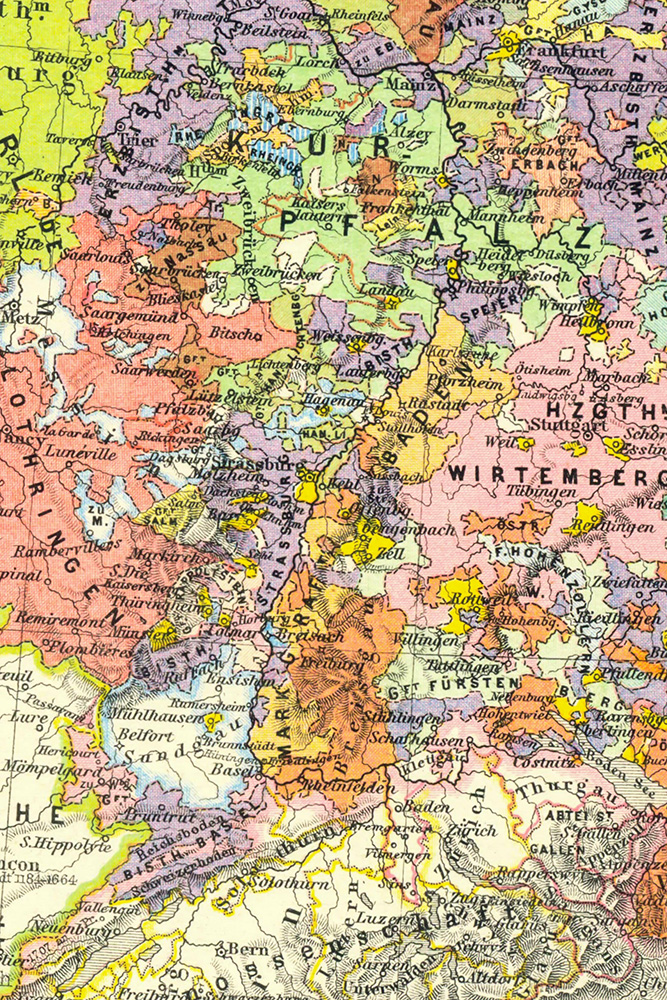

The territorial puzzle of the Upper Rhine region, including Alsace

Coats of arms of the Habsburgs and the Counts of Ferrette, Town Hall of Ferrette © French Moments

1. A Region at the Heart of the Empire

Alsace had been part of the Empire since the early Middle Ages.

From Charlemagne to Otto I, the Hohenstaufen and later the Habsburgs, imperial authority was present — but never consistent.

The Great Interregnum (1250–1273), a period of political instability within the Empire, deepened this fragmentation.

The bishops of Strasbourg and Basel, powerful abbeys such as Murbach and Ebersmunster, and numerous noble families carved out their own semi-independent fiefs.

This dispersion of power made Alsace both coveted and difficult to govern.

Strategically positioned between France and the Empire, it served as a corridor of invasion as much as a crossroads of trade.

Each town had its own customs, its dialect (often Alemannic), and its local laws.

On the eve of the Peace of Westphalia, the region was not a state, but rather an entanglement of micro-territories — a true mosaic of the Empire.

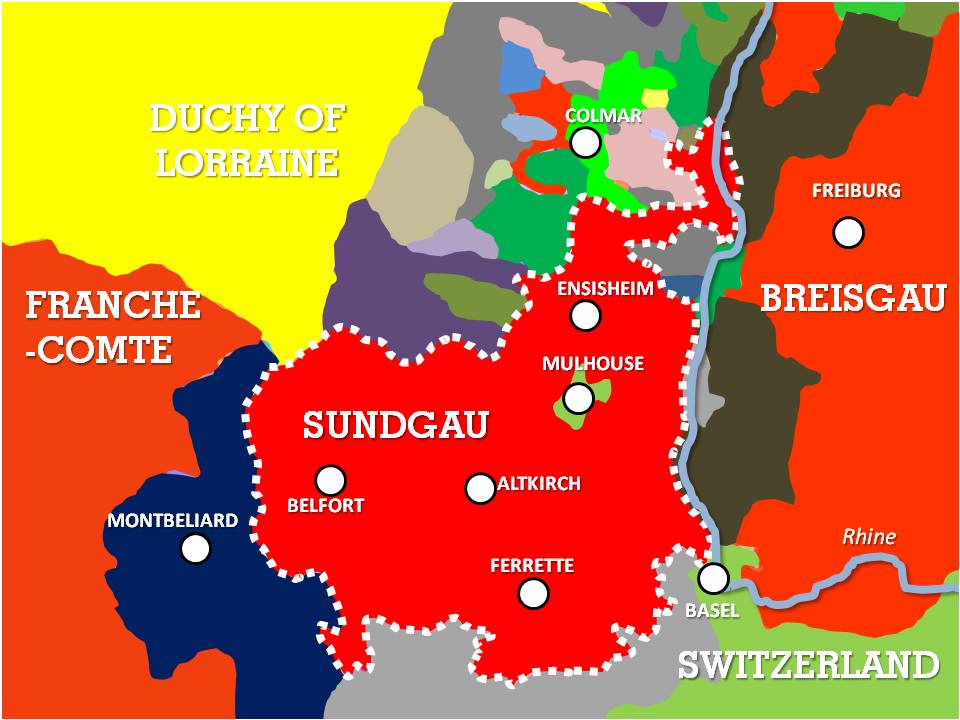

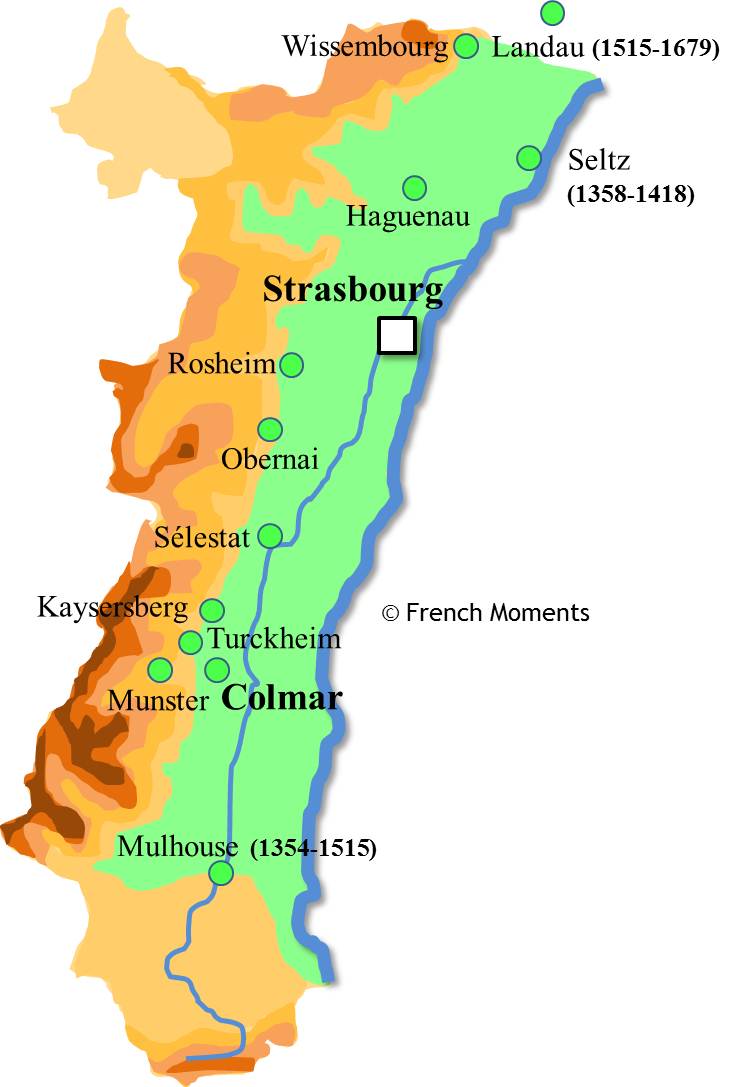

Map: Note the small enclave of Mulhouse within the Habsburg possessions in red © French Moments

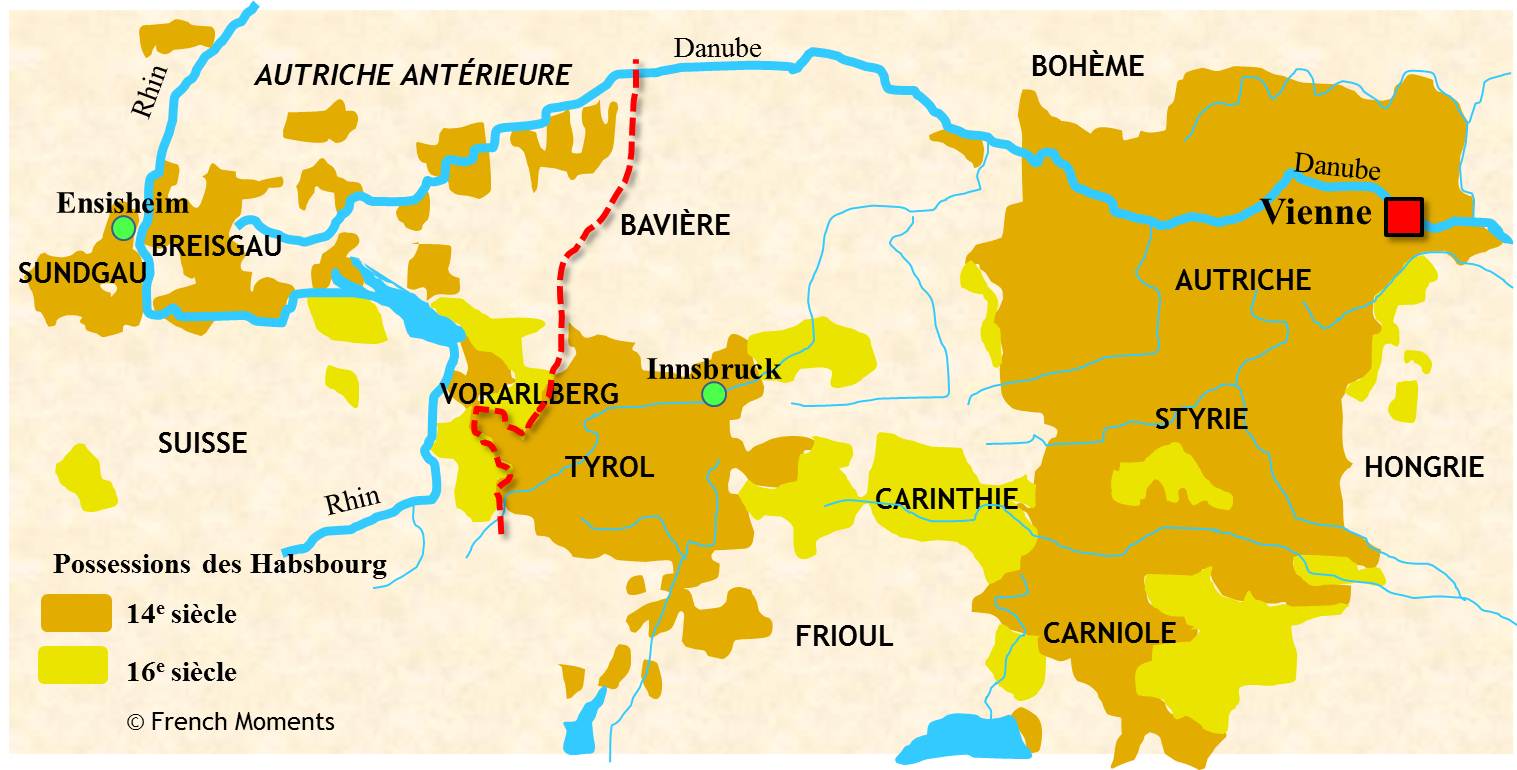

2. Habsburg Power and Further Austria

The Habsburgs had dominated Upper Alsace since the fourteenth century.

Their domain, known as Vorderösterreich or “Austria Anterior”, comprised the Sundgau — including the County of Ferrette and several seigneuries around Belfort.

Map: Austria Anterior before 1648

Administered from Ensisheim, this region represented the westernmost part of the Austrian possessions, separated from the rest of the Empire by the Rhine and the Vosges.

The Habsburgs had succeeded in maintaining firm authority in the Sundgau, but their influence went no further.

The Imperial cities of northern and central Alsace — Strasbourg, Colmar, Sélestat, Haguenau — fiercely resisted any attempt at control.

They answered directly to the Emperor, not to any local lord.

This was the principle of Imperial immediacy, which guaranteed them political and judicial autonomy.

Often prosperous thanks to the wine and textile trade, these free cities formed a bastion of urban liberties at the heart of the Empire.

3. The Dualism Between Upper and Lower Alsace

Alsace’s political geography was marked by a deep dualism.

- Upper Alsace (Haute-Alsace, in the south, around Thann and Altkirch) belonged directly to the Habsburgs.

It was a mediated territory — subject to a lord rather than to the Emperor. - Lower Alsace (Basse-Alsace, in the north, around Strasbourg, Sélestat and Haguenau) comprised immediate entities — free cities, abbeys and ecclesiastical fiefs under Imperial authority alone.

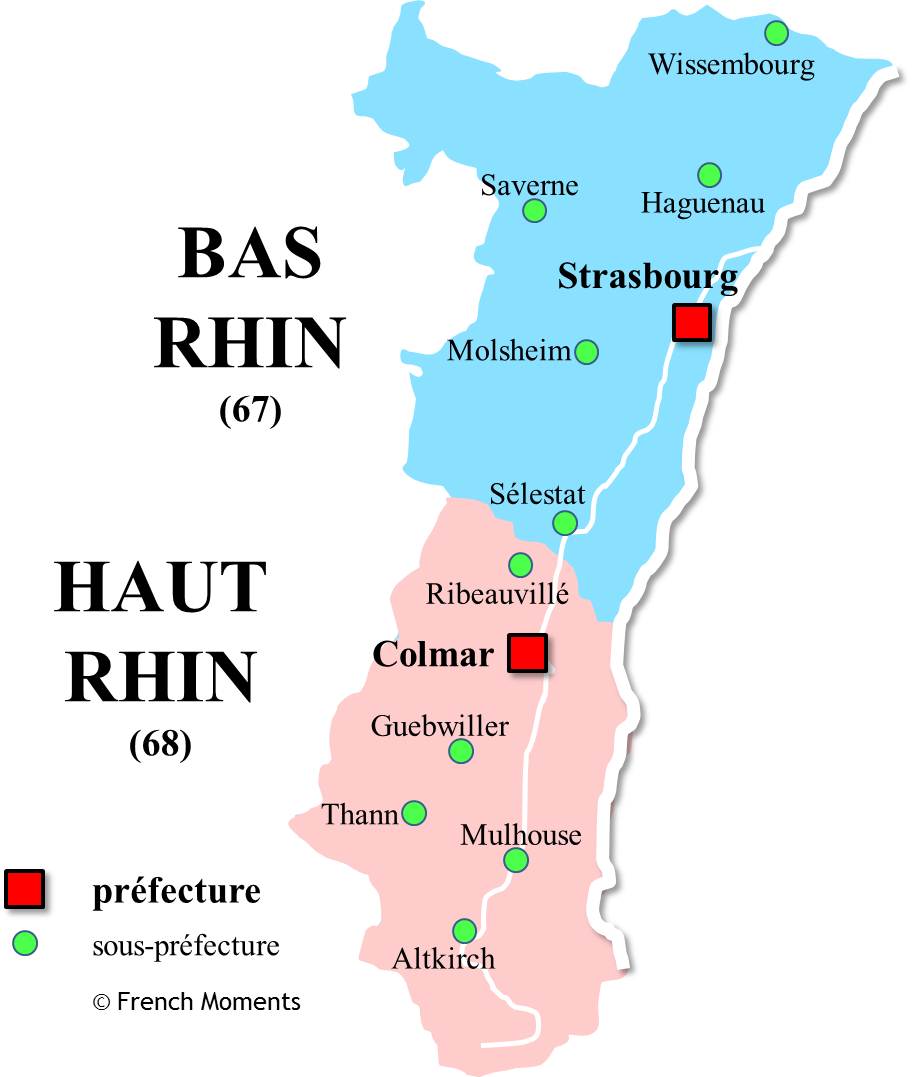

Map: Upper and Lower Alsace — a division that foreshadowed today’s Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin departments

This dual structure explains the structural weakness of Austrian power in Alsace.

Despite three centuries of presence, the Habsburgs had never managed to unify the region.

They ruled over a scattered collection of fiefs, without true territorial cohesion — a reality that made France’s task in 1648 far easier.

There was no unified state to conquer, only a series of feudal rights to acquire.

4. A Landscape Ripe for French Diplomacy

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Thirty Years’ War plunged Alsace into chaos.

Imperial and Swedish armies crossed the region repeatedly, while French troops, under Richelieu and later Mazarin, began intervening in the 1630s.

France established garrisons in several key towns, notably Belfort, Breisach, and Landau.

By the time negotiations opened for the Peace of Westphalia, France already held a position of strength.

Richelieu had understood that controlling Alsace was the key to securing the Rhine frontier and undermining Habsburg power once and for all.

But achieving this goal required great diplomatic finesse.

Legally speaking, Alsace was not a single territory to be ceded, but rather a layered patchwork of feudal rights belonging to various entities.

Thus, on the eve of 1648, Alsace was at once fragmented, German and Imperial — a land of precarious balances, where Habsburg authority coexisted with the independence of the free cities.

This unstable framework would serve as a springboard for French expansion: the Peace of Westphalia would transform this political patchwork into a territory placed under French sovereignty— at least in theory.

The ruins of Landskron Castle © French Moments

The Peace of Westphalia and the Cession of Alsace to France

The Treaties of Westphalia, signed in October 1648, brought the Thirty Years’ War to an end and inaugurated a new political order in Europe.

In the case of Alsace, however, they opened a period of ambiguity, compromise, and conflicting legal interpretations.

Alsace was not annexed in a single stroke; it drifted gradually into the orbit of the French crown, through a subtle interplay of feudal law and diplomacy.

Proclamation of the Peace of Westphalia in Münster

1. The Treaty of Münster and Article LXXV: An Ambiguous Cession

The key text concerning Alsace appears in Article LXXV of the Treaty of Münster, signed between France and the Holy Roman Empire on 24 October 1648.

By this article, Emperor Ferdinand III ceded to King Louis XIV of France and his successors:

“The Landgraviate of Upper and Lower Alsace, the Sundgau, and the Provincial Prefecture over the ten towns and places included.”

At first glance, the phrase seems clear — yet it concealed a remarkable legal ambiguity.

The French diplomats, led by the Duke of Longueville, Abel Servien and Claude d’Avaux, had deliberately maintained a degree of vagueness in the wording.

Instead of demanding precise borders or detailed definitions, they preferred a general formula: a cession of “all rights of direct lordship and sovereignty” previously held by the Habsburgs.

This strategy of “constructive ambiguity” was intentional.

It left the door open for broader interpretations in the future.

The aim was long-term: not to obtain all of Alsace immediately, but to establish a legal foundation that Louis XIV could later exploit through policy and diplomacy.

2. Two Opposing Interpretations: Imperial and French

From the moment the treaties were signed, two radically different interpretations emerged.

The French (maximalist) view held that the cession amounted to full sovereignty.

France, according to this reading, became the direct heir of the Habsburgs, effectively replacing the Emperor himself.

Alsace, therefore, ceased to belong to the Holy Roman Empire and passed entirely under the French crown.

The Imperial (minimalist) view, defended by German jurists, claimed the opposite: France had obtained only a limited feudal overlordship.

In other words, it replaced the Habsburgs in their lordly rights over certain fiefs, but could not claim a complete break with the Imperial order.

The free cities — such as Strasbourg or Colmar — were, in theory, to remain under the authority of the Holy Roman Empire.

These irreconcilable interpretations would dominate the political landscape throughout the later seventeenth century.

They explain why, despite the treaty’s signature, French sovereignty in Alsace remained largely theoretical for decades.

On the ground, the symbols of Imperial power — coats of arms, privileges, titles — continued to coexist alongside the insignia of the French king.

Negotiations of the Peace of Westphalia

3. French Motives: A Calculated Diplomacy

Behind the cautious diplomatic language lay a carefully crafted strategy by the French monarchy.

Since the time of Richelieu, the goal had been clear: break the Habsburg encirclement and secure the Rhine frontier, now vital to the kingdom’s defence.

Alsace offered both opportunities at once:

- to weaken Habsburg power, and

- to control the Rhine crossings that linked the Spanish Netherlands to Austria.

Mazarin, Richelieu’s successor, sent seasoned diplomats to Münster, assisted by experts in Imperial law such as Théodore Godefroy.

Their task was to navigate the complexities of German feudal law.

Their mission was not so much to draw fixed borders as to secure a flexible legal framework that would allow the French king to act later — with full legitimacy.

This approach paid off.

Thanks to these carefully worded ambiguities, the French crown could later invoke the 1648 text to justify further annexations and interventions — notably during Louis XIV’s policy of “Reunions.”

4. A Transfer of Rights Rather Than Territories

Contrary to the image of a territorial conquest, the Peace of Westphalia primarily enacted a transfer of rights and titles.

France did not receive a unified land, but rather a set of legal prerogatives inherited from the Habsburgs:

- the Landgraviate of Upper and Lower Alsace,

- the Sundgau (including Belfort and Ferrette), and

- the Landvogtei, the provincial prefecture overseeing the ten Imperial cities of the Décapole.

At first sight, these rights seemed purely administrative and symbolic, but they granted France the legal authority to gradually intervene in the affairs of these cities and lordships.

They became the legal levers through which an effective sovereignty would be patiently built over the following decades.

The Witches’ Gate at Châtenois, near Sélestat © French Moments

5. An Alsace in Suspension

In 1648, Alsace was neither fully French nor entirely Imperial.

On paper, the King of France held legal sovereignty; in practice, the institutions of the Empire still prevailed.

The towns continued to mint their own coins, elect their magistrates, administer justice under German law, and keep their records in German.

This hybrid situation created a political vacuum, which the French monarchy sought to fill — not by war, but through a policy of progressive centralisation.

The royal administration advanced step by step: first in the Sundgau, then in the Décapole, before finally reaching Strasbourg at the end of the century.

Thus, the Peace of Westphalia did not instantly make Alsace French; it merely opened the door.

The region’s transformation, begun at Münster, would continue for more than thirty years — a slow process of political, administrative and cultural integration, unique in European history.

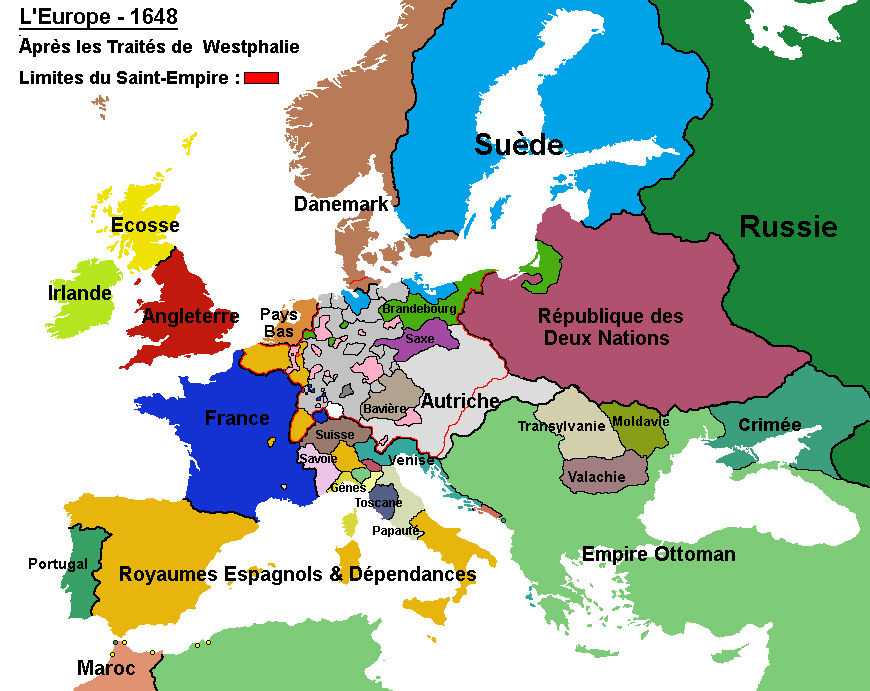

Europe after 1648 – by Helio74100 - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] via Wikimedia Commons

The First Effects of the Peace of Westphalia on Alsace (1648–1659)

The signing of the Peace of Westphalia did not immediately turn the region into French territory.

Between 1648 and the late 1650s, the situation remained confused — a mixture of military occupation, preserved Imperial privileges, and early attempts at administrative centralisation.

Alsace became a laboratory of coexistence between two political systems: that of the Holy Roman Empire and that of the Kingdom of France.

1. The Immediate Integration of the Sundgau and Belfort

The Sundgau, a region south of Mulhouse, was the only part of Alsace to pass unreservedly under French control following the treaties.

Formerly a direct Habsburg possession, it belonged to Austria Anterior and held no Imperial immediacy.

Its cession to France, therefore, raised no legal ambiguities and no international disputes.

View over the eastern Sundgau © French Moments

From 1648 onwards, the French monarchy established its first garrisons and administrators in the region.

The County of Ferrette and the strategic stronghold of Belfort were integrated into the royal domain, forming the initial nucleus of French presence in Alsace.

Mazarin ordered the restoration of fortifications, placed the military command under French authority, and appointed intendants to supervise local finances.

This first step proved decisive: it gave France both a military foothold on the left bank of the Rhine and a legal base for future interventions in neighbouring territories.

The Sundgau thus became the bridgehead of French expansion in Alsace.

2. The Preservation of Imperial Privileges in the Décapole

The rest of the province, however, proved far more complex to integrate.

The ten cities of the Alsatian Décapole — Haguenau, Colmar, Sélestat, Obernai, Kaysersberg, Turckheim, Rosheim, Wissembourg, Munster, and Landau — enjoyed special privileges guaranteed by Imperial law since the fourteenth century.

They formed an urban confederation loyal to the Emperor and fiercely protective of their autonomy.

The cities of the Alsatian Décapole © French Moments

The Peace of Westphalia had stipulated that France would inherit the Emperor’s sovereign rights, but without abolishing the cities’ liberties.

As a result, the towns continued to govern themselves under their own laws, to hold municipal councils in German, and to administer justice according to Imperial codes.

The King of France, officially a protector, found himself in a paradoxical position: exercising authority without direct power.

In Colmar and Sélestat, the inhabitants viewed royal representatives with suspicion.

Local authorities insisted that French troops be quartered outside the city walls to prevent what they called a “disguised occupation.”

This caution reflected the political tension of the time: France had to balance long-standing municipal traditions with the assertion of its new sovereignty.

3. Strasbourg: The Great Absentee from the Treaties

Among Alsace’s major cities, Strasbourg occupied a special place.

A Free Imperial City since the thirteenth century, it was not included in the cession of 1648.

Its representatives had taken no part in the negotiations, and the city was nowhere mentioned in the articles of the Treaty of Münster.

Strasbourg during the Thirty Years’ War, 1644

Strasbourg took advantage of this omission to preserve its independence, even strengthening its defences after the war.

The bishop, who supported France, was sidelined in favour of a Protestant magistrate loyal to the Empire.

The city continued to flourish economically and culturally, attracting students, printers, and merchants from across Europe.

But its strategic position on the Rhine made it an obvious target for French ambitions — something Louis XIV would not forget.

4. A Fragile Balance Between Empire and Kingdom

During the first decade after Westphalia, Alsace lived in an in-between state.

The King of France was recognised as sovereign, yet the Imperial institutions continued to function.

Bishoprics, abbeys, and free cities still corresponded with Vienna, while royal intendants reported to Paris.

This administrative dualism created confusion:

- Taxes were collected according to old Imperial regulations.

- Legal cases were argued in German before judges loyal to the Emperor.

- Sermons were often preached in Alsatian dialect — or Latin in monastic areas.

For the population, already worn down by war, little seemed to change in daily life.

The armies were gone, peace had returned, but the shift in authority felt distant and abstract.

5. France Settles In for the Long Term

Despite these slow beginnings, the 1650s laid the foundations for France’s lasting presence in Alsace.

Mazarin, and later Colbert, encouraged the reconstruction of infrastructure and the revival of trade along the Rhine.

French military engineers began modernising fortifications — foreshadowing the great works of Vauban a few decades later.

Gradually, French-speaking administrators settled in Ensisheim and Colmar, while official correspondence started to be written partly in French.

This change, discreet but steady, marked a smooth transition toward a new political order.

Alsace still stood between two allegiances, but the Peace of Westphalia had set in motion an irreversible process — the slow transformation of an Imperial land into a French province.

The fortified gate of Dieffenthal © French Moments

From Ambiguity to Sovereignty: The Consolidation of French Power (1659–1679)

In the aftermath of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace, France held legal legitimacy, but not yet real authority.

It would take three decades of diplomacy, administration, and political manoeuvring to transform theoretical sovereignty into effective control.

Between 1659 and 1679, the French monarchy undertook a patient process of integration — legal, military, and symbolic.

The Koïfhus, former customs house of Colmar © French Moments

1. The Landvogtei: A Tool Serving France

One of the key consequences of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace was the transfer of the Landvogtei — the provincial prefecture — from the Habsburgs to the King of France.

Created during the Imperial period, this office represented the highest authority over the ten cities of the Décapole.

By acquiring it, France became the official “protector” of the Imperial cities — a position which, on paper, did not alter their autonomy, but in practice placed their administration under royal oversight.

From the 1660s onward, Paris began appointing representatives responsible for ensuring the treaty’s implementation.

These officials, often Alsatian by birth but trained at court, acted as intermediaries between the municipal authorities and the central government.

They gradually introduced French administrative practices: bilingual registers, official correspondence addressed to the King, and participation in fiscal decisions.

Thus, the Landvogtei became the cornerstone of a “sovereignty in the making” — France never abolished the old institutions but quietly replaced them, transforming Imperial authority into royal authority.

2. The Sovereign Council of Alsace: The King’s New Justice

In 1657, Mazarin established the Sovereign Council of Alsace, initially in Ensisheim, later moved to Colmar in 1698.

Modelled directly on the French Parlements, this institution symbolised the crown’s determination to assert its judicial authority over the region.

It replaced the former Imperial courts and became the province’s highest tribunal.

The Council’s role was to:

- Judge civil and criminal cases in the final appeal.

- Standardise judicial procedures.

- Gradually introduce French law, while respecting certain local customs.

Its creation marked a decisive step: justice was no longer rendered in the Emperor’s name, but in the name of the King of France.

Over time, this institution helped to “Frenchify” legal practices and affirm the supremacy of royal power over the old Imperial framework.

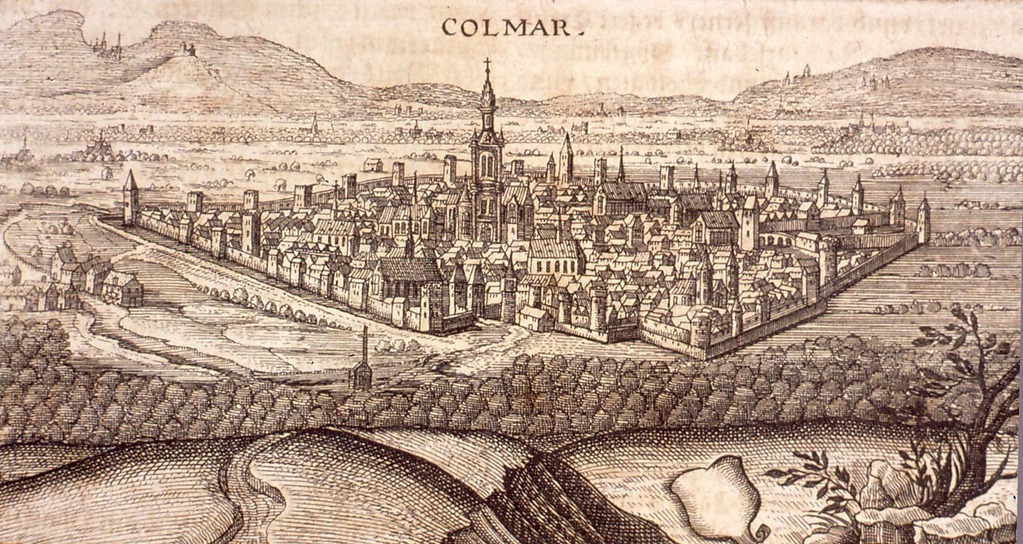

Colmar around 1750

3. The Policy of “Reunions”: Extending Sovereignty Through Law

Under Louis XIV, French diplomacy entered a new phase — the Reunions (1679–1681).

This ingenious mechanism invoked the Peace of Westphalia to claim additional territories supposedly linked, directly or indirectly, to the rights ceded in 1648.

The King created special Chambers of Reunion, composed of jurists tasked with examining old charters and determining which lands, abbeys, or lordships could “legally” be incorporated into France.

This policy, outwardly legalistic but clearly political, allowed Louis XIV to justify the annexation of several localities without open warfare.

Between 1673 and 1679, several cities of the Décapole — including Colmar, Haguenau, and Sélestat — came under direct royal control.

French troops replaced Imperial garrisons, and local magistrates swore allegiance to the King.

The Treaty of Nijmegen (1679) formalised these acquisitions, bringing an end to Habsburg dominance over most of Alsace.

4. A Gentle but Determined Centralisation

This period was marked by the growing influence of the royal intendants, the true representatives of the King in the provinces.

They oversaw the collection of taxes, the maintenance of roads, military discipline, and even public morality.

They also acted as a bridge between Paris and the often still-cautious local authorities.

The French monarchy pursued a policy of integration without brutality: it allowed municipal privileges, local languages, and religious customs to remain, while gradually imposing its own presence.

Alsatian notables were invited to sit on the Sovereign Council, to form marriages with the French nobility, or to send their sons to study in Paris.

This pragmatic method proved effective.

In the space of twenty years, Alsace, while retaining its distinct character, became familiar with French administrative structures.

It remained bilingual, but began to take part in the political and economic life of the kingdom.

5. The Final Stage Before Strasbourg

On the eve of the 1680s, French sovereignty over Alsace was almost complete.

The Sundgau, the Décapole, and Lower Alsace were now administered from Colmar; taxes were collected on behalf of the King, and courts rendered justice “in His Majesty’s name.”

Only Strasbourg remained outside this framework.

As a Free Imperial City, it retained its independence within the Holy Roman Empire, its Protestant council, its university, and its economic autonomy.

But its strategic position on the Rhine made it the final missing piece of the puzzle.

Louis XIV knew that to secure France’s eastern frontier once and for all, Strasbourg would eventually have to join the French crown.

Thus, between 1659 and 1679, France progressed from theoretical sovereignty to real control.

Strasbourg Cathedral © French Moments

The Peace of Westphalia had provided the legal foundation; Louis XIV turned it into a political instrument.

Through administration, justice, and diplomacy, Alsace became firmly anchored within the Kingdom of France — not by force, but through methodical persistence.

The Completion of the Union: Strasbourg, Mulhouse and the Remaining Fiefs

By the end of the seventeenth century, Alsace’s integration into the Kingdom of France was almost complete.

The Peace of Westphalia and Alsace had paved the way for French sovereignty, but a few territories still escaped Paris’s control.

Among them, Strasbourg, Mulhouse, and several small fiefs stood out for their particular legal status and enduring attachment to the Imperial order.

Eager to unify his kingdom and secure the Rhine frontier, Louis XIV sought to bring these last enclaves under the crown — always relying on the legitimacy inherited from 1648.

1. Strasbourg: The Key to the Rhine

Since the signing of the Peace of Westphalia, Strasbourg had remained an independent Free Imperial City.

Prosperous, well-governed, and proud of its liberties, it served as a model for other Rhenish cities.

Its council, dominated by Protestant patrician families, rejected any interference from France.

With its university, cathedral, and flourishing printing industry, Strasbourg was one of the intellectual centres of the Holy Roman Empire.

The picturesque Rue de Rohan, Strasbourg © French Moments

To Louis XIV, however, Strasbourg was a strategic anomaly: a major city straddling the Rhine, it remained the only non-French stronghold between Lorraine and Switzerland.

Faithful to his policy of border unification, the king decided to act — not through war, but by a calculated show of force.

In September 1681, the troops of Marshal de Boufflers, stationed at Kehl, crossed the Rhine and surrounded the city.

The magistrates of Strasbourg, recognising the balance of power, chose to surrender without resistance.

On 30 September 1681, Strasbourg opened its gates to Louis XIV, who made his formal entry a few weeks later.

The Treaty of Ryswick (1697) would later confirm the annexation.

Wishing to win over the inhabitants, the king guaranteed freedom of Protestant worship, preserved local institutions, and ordered that sermons in the cathedral be delivered alternately in French and German.

He also restored the cathedral to Catholic worship — a highly symbolic gesture, yet carried out without violence.

The integration of Strasbourg marked the territorial completion of Alsace’s union with France.

For the first time, the left bank of the Rhine, from Basel to Lauterbourg, was entirely under French control.

2. Mulhouse: The Republic Allied with Switzerland

Unlike Strasbourg, Mulhouse retained its independence for much longer.

A member of the Alsatian Décapole in the Middle Ages, the city left the confederation in 1515 to ally itself with the Swiss Confederation, whose Reformed faith and economic interests it shared.

This alliance, strengthened by treaties of mutual assistance, made Mulhouse a fully independent republic, recognised by the Empire and respected by France.

Place de la Réunion, Mulhouse © French Moments

The Peace of Westphalia and Alsace made no mention of Mulhouse: the city was neither a Habsburg possession nor a fief of the Landgraviate.

It therefore lay outside the scope of the 1648 cession.

Protected by its Swiss allies, Mulhouse remained beyond French control for more than a century.

Nevertheless, the city maintained close ties with the kingdom.

Its textile workshops traded with Colmar and Basel, and many Mulhousians served as engineers or officers in the royal army.

Yet the small republic clung to its autonomy, its privileges, and its Reformed faith.

It was only in 1798, under diplomatic pressure from Revolutionary France, that Mulhouse voted voluntarily to join France — ending nearly three centuries of independence.

3. Riquewihr and the Independent Fiefs

Alongside Strasbourg and Mulhouse, several lordships and fiefs in Alsace remained under the authority of German princes.

Among them was Riquewihr, a possession of the Count of Württemberg-Montbéliard.

These territories, legally attached to the Holy Roman Empire, were not included in the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace.

The French monarchy, therefore, sought to integrate them into the kingdom without triggering diplomatic incidents.

Riquewihr from above © French Moments

In the case of Riquewihr, Louis XIV invoked the policy of Reunions, arguing that the Count of Württemberg owed homage to the French king for his Alsatian lands.

In 1680, the town was effectively attached to France, but retained its privileges, municipal autonomy, and the right to administer justice according to local custom.

Riquewihr thus remained an island of Germanic culture within the kingdom, loyal to its dual heritage.

4. Securing the Rhine and the End of a Shifting Border

With the capture of Strasbourg and the integration of the last seigneuries, France finally reached its natural frontier along the Rhine — an objective pursued since the time of Richelieu.

The Peace of Westphalia and Alsace had provided the legal foundation; Louis XIV turned it into a geographical reality.

The Rhine became a fortified defensive line.

Vauban built or modernised the fortresses of Strasbourg, Neuf-Brisach, and Huningue, transforming the region into a true stone bastion.

Beyond its military value, this unification profoundly changed the perception of Alsace: it was no longer an Imperial borderland, but a French frontier province, guarding the kingdom’s eastern edge.

5. A Turning Point in Alsatian Identity

This long political integration gradually reshaped local mindsets.

Urban elites began to look toward Paris, while local nobles gained positions in the royal army or judiciary.

French, initially an administrative language, became the language of prestige.

Yet in the villages, Alemannic dialects and Germanic traditions remained deeply rooted.

This coexistence would become a defining feature of Alsatian identity.

Traditional Alsatian costume in Kaysersberg © French Moments

Now subjects of the French king, the Alsatians still maintained a strong attachment to their local freedoms and cultural heritage.

The union established by the Peace of Westphalia did not bring assimilation, but rather a harmonious coexistence of two traditions — Latin and Germanic, royal and Imperial.

By 1681, the circle was complete: Strasbourg had joined the kingdom, the Sundgau had been French for more than thirty years, and most of the fiefs had recognised royal sovereignty.

Through the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace, France had achieved, without war, one of the most profound territorial transformations in its modern history.

The Consequences of the Peace of Westphalia on Alsace: Administration, Law and Religion

Let us summarise what we have seen.

The Peace of Westphalia and Alsace did not merely alter borders; it transformed daily life, political organisation, and the religious balance of an entire region.

In less than a century, Alsace evolved from a tangle of Imperial authorities into a province structured according to the principles of the French kingdom — without losing its distinctive identity.

This slow, cautious transition was one of the most remarkable in early modern Europe.

1. A Province in Administrative Construction

After 1648, France set about reorganising Alsace along the lines of its other provinces, while taking into account its particularities.

Mazarin and later Colbert understood that any abrupt break with existing institutions had to be avoided.

The aim was not to impose the French system by force, but to overlay royal administration onto local governance.

The Role of the Sovereign Council of Alsace

Established in Ensisheim in 1657 and later transferred to Colmar, the Sovereign Council of Alsace became the province’s highest judicial and administrative authority.

The Koïfhus – former Customs House, Colmar © French Moments

It embodied the monarchy’s authority in the region: cases were judged “in the King’s name”, even when the law applied remained Germanic.

The Council’s duties included:

- settling disputes between towns and lordships,

- supervising taxation and the enforcement of royal ordinances,

- and gradually integrating local laws and customs into the framework of French law.

This coexistence between two legal systems gave rise to a hybrid regime: the King governed under French law, but the courts continued to respect municipal statutes inherited from the Empire.

This model of compromise — typically Alsatian — avoided uprisings and ensured a smooth transition.

Intendants and Royal Centralisation

From the 1660s, intendants were sent to Colmar, Haguenau, and Strasbourg.

Their mission was to supervise finances, standardise weights and measures, reorganise taxation, and manage local elites.

Under their supervision, new land registers were drawn up, roads improved, and customs reorganised along the Rhine.

Through their efforts, the French administration turned a feudal mosaic into a coherent province while maintaining respect for local particularities.

Alsace became a showcase of French administrative skill: firm yet flexible.

2. The Partial Retention of Local Law

One of the most striking consequences of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace was the preservation of Germanic legal traditions.

Unlike other newly annexed regions, France allowed much of the local civil and criminal law to remain.

German law continued to apply in many civil matters — inheritance, property, and contracts.

Legal records were often written in German; magistrates used Imperial terminology, and notaries kept bilingual registers.

Royal ordinances were translated for rural populations, many of whom spoke no French.

Bilingual street sign, Rue des Potiers, Kaysersberg © French Moments

This arrangement produced a mixed legal culture, combining German precision with French pragmatism.

Even today, this legacy endures in the local law of Alsace-Moselle — a direct descendant of this long historical compromise.

3. The Religious Simultaneum: Shared Churches and Cautious Tolerance

At the time of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace, the region’s towns were mostly Protestant, while the countryside remained largely Catholic.

The 1648 text upheld the principle of freedom of worship — a rare concept in seventeenth-century Europe.

Determined to preserve peace in this sensitive borderland, Louis XIV applied this principle with measured pragmatism, quite unlike his policy elsewhere in France.

From 1684, he introduced in many parishes the system known as the Simultaneum: Catholics and Protestants shared the same church building, using it at different times of day.

The fortified church of Hunawihr in spring © French Moments

This arrangement, unique within the kingdom, was intended to ease confessional tensions.

It avoided forced conversions but occasionally provoked disputes, especially in the Lutheran north.

Overall, the monarchy remained tolerant in Alsace, aware that a harsher policy might reignite anti-French resentment in the Empire.

This coexistence, often cited as a legacy of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace, helped shape a lasting culture of dialogue and tolerance in the region.

4. Gradual Cultural Francisation

Culturally and linguistically, change came slowly.

French first took root in administration, official correspondence, and the army, but remained absent from everyday life for decades.

In the towns, German remained the language of business, justice, and education.

Bilingual street sign in Kaysersberg © French Moments

Priests, pastors, and notaries preached and wrote in local dialects.

Yet growing contact with the crown — through soldiers, magistrates, and merchants — gradually spread the use of French.

By the late seventeenth century, the urban elite read Molière and Racine, and some Alsatian families sent their sons to study in Paris.

This slow linguistic shift accompanied political integration without erasing the region’s Germanic identity.

5. Restored Religious and Economic Stability

Another key outcome of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace was economic revival.

After decades of devastation, peace brought back harvests, trade, and craftsmanship.

The fairs of Strasbourg and Colmar resumed; the wine and timber trade revived along the Rhine; and the reconstruction of churches and bridges symbolised a return to prosperity.

Under Colbert, the region benefited from major investment: the creation of textile workshops, the exploitation of Vosges forests, and the improvement of river routes.

This prosperity strengthened local attachment to French stability — even though many people continued to see themselves, above all, as Alsatians.

6. A Lasting Balance Between Two Heritages

By the end of the seventeenth century, Alsace had achieved a rare balance.

Royal authority was recognised, taxes were collected for the King, and justice was administered in his name — yet the region’s language, customs, and mindset remained deeply influenced by Germany.

This equilibrium between loyalty and autonomy, between French governance and Imperial memory, became the key to Alsatian identity.

Born of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace, it turned the region into an early model of peaceful coexistence and measured integration — long before the idea of a united Europe.

The Rodolphe of Habsburg fountain, Ensisheim © French Moments

A Lasting Legacy: Alsace Between Two Worlds

More than three centuries after their signing, the Peace of Westphalia still shapes the region’s memory and identity.

The treaties did not simply fix borders — they forged a culture of coexistence, compromise, and dialogue in a land long shared between two great European civilisations.

Through this singular history, Alsace became a symbol of unity in diversity.

1. An Identity Shaped by the Border

Alsace has always lived with its border — not as a scar, but as a horizon.

The Peace of Westphalia made it a land of transition, where the French language meets the German dialects, Catholic tradition mingles with Protestant reform, and Latin spirit blends with Rhenish rigour.

Over the centuries, this duality became a defining feature of the Alsatian soul.

Where other regions saw borders as walls, Alsace turned them into bridges: between Paris and Vienna, the Rhine and the Vosges, France and Germany.

It is precisely this spirit that later made Alsace central to the Franco-German rapprochement of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries — and, ultimately, to the very idea of European unity.

The Regency Palace, Ensisheim © French Moments

2. A Land of Tolerance Born of Westphalia

One of the deepest legacies of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace was the emergence of a culture of tolerance.

By ending the Wars of Religion and establishing freedom of worship, the treaties ingrained a reflex of coexistence into the region’s collective character.

Catholics and Protestants learned to share space — sometimes the same church — and often the same values of diligence, order, and solidarity.

This religious pluralism made Alsace unique within France.

While the rest of the kingdom endured the harsh consequences of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), the Protestant churches of Alsace remained open, protected by the promises made in 1648.

The region became a refuge for religious minorities, reinforcing its reputation as a land of balance and freedom.

3. A Political and Legal Laboratory

The Peace of Westphalia and Alsace also left a distinctive legal and political structure.

French administration overlaid existing local institutions — without erasing them.

From this superimposition emerged a hybrid model, halfway between Roman law and Germanic custom.

In the eighteenth century, the intendants and magistrates of the Sovereign Council of Alsace ranked among the most effective in France, precisely because they combined two traditions:

- French centralisation and administrative hierarchy,

- German legal rigour and discipline.

This legacy outlived the Revolution.

Even today, some features of Alsace-Moselle’s local law — including the organisation of religious communities, associations, and social welfare — trace their roots back to this post-1648 compromise.

Thus, the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace left not only a moral legacy but also a living legal one, adapted to a plural society.

4. A Memory Etched in Stone

The landscapes of Alsace still bear witness to this formative era.

Vauban’s fortresses, the town halls of the Décapole, and the double-choired churches recall both the tensions and alliances of the seventeenth century.

In Strasbourg, the Cathedral and Rohan Palace symbolise at once medieval faith and royal grandeur.

In Colmar, the statue of Bartholdi overlooks a city where French and German once mingled on shop signs, in schools, and in courtrooms.

Every stone, every spire, every square tells a story of negotiation and balance — that of a region which became French without losing its Germanic soul.

Place Kléber, Strasbourg © French Moments

5. From Westphalia to Europe

The legacy of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace extends far beyond the regional sphere.

The principles established in 1648 — state sovereignty, balance of power, non-intervention, and religious tolerance— became the cornerstones of modern diplomacy.

And it is in Alsace, three centuries later, that these ideals found their most tangible continuation: Strasbourg, chosen as the seat of both the Council of Europe and the European Parliament, perfectly embodies the enduring Westphalian spirit.

6. A Proudly Dual Identity

Even today, Alsace embraces its dual identity — and that duality remains its greatest strength.

French in culture and institutions, Germanic in language and tradition, the region perfectly illustrates the European motto: United in Diversity.

The story born of the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace is not one of rupture, but of continuity — the slow union of two heritages that were never truly incompatible.

From this fusion emerged a distinctive way of being, balanced between loyalty and openness, memory and modernity— in short, a profoundly Alsatian way of life.

Strasbourg: a cosmopolitan city! © French Moments

Conclusion

The Peace of Westphalia and Alsace marked far more than a diplomatic episode: it transformed the destiny of a region — and, through it, the face of Europe itself.

By ending Habsburg rule and integrating Alsace into the French kingdom, these treaties created a unique province — French in sovereignty, yet deeply Germanic in culture and language.

This union was not achieved through conquest, but through a gradual process of transformation, rooted in law, diplomacy, and political foresight.

Between 1648 and the close of the seventeenth century, France accomplished one of the rare examples of peaceful integration in early modern Europe.

It preserved local freedoms, languages, and faiths, while firmly establishing its institutions.

This pragmatic approach explains the enduring success of Alsace’s union with France.

The citadel overlooking the fortifications of Belfort © French Moments

In the long run, the Peace of Westphalia and Alsace helped forge a distinct regional identity based on coexistence and dialogue.

Religious tolerance, bilingualism, and dual culture — far from weakening national unity — have enriched France’s diversity.

From the meeting of Latin and Rhenish worlds emerged a borderland that became, over time, a bridge between nations.

Finally, the spirit of Westphalia — that of compromise, negotiation, and peace — finds its most vivid expression in Alsace today.

From Strasbourg to Colmar, from Vauban’s fortresses to the European institutions, the region embodies the vision of a Europe built not by conquest, but through dialogue and understanding.

Thus, the story that began in Münster and Osnabrück nearly four centuries ago still lives on in the heart of Alsace — a peace signed with ink, not blood, which succeeded, better than any war, in uniting two worlds into one.

Want to Read More?

A few related blog articles you might enjoy:

Sources

Here are the sources consulted for this study. If you have any clarifications or corrections to make to this study, please leave a comment below!

- Traités de Westphalie et système international: https://www.ileri.fr/explorer-librement-le-monde-les-traites-de-westphalie

- Conséquences des Traités de Westphalie sur l'Europe et le Saint-Empire : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trait%C3%A9s_de_Westphalie

- Cession Alsace Traité de Münster (Article LXXV) : https://mjp.univ-perp.fr/traites/1648westphalie2.htm

- Négociations sur l'Alsace et rôle des experts à Münster : https://books.openedition.org/pur/167851?lang=en

- Rédaction des articles du traité de Münster (Alsace et Trois-Évêchés) : https://books.openedition.org/enc/4387

- Définition et organisation de l'Autriche Antérieure (Vorderösterreich) : https://dhialsace.bnu.fr/wiki/Autriche_ant%C3%A9rieure

- Habsbourg et échec de la création d'un territoire uni en Alsace : https://www.deuframat.de/fr/europeisation/leurope-des-regions/leurope-une-et-divisee-regards-historiques-sur-/un-territoire-sans-frontieres-bien-delimitees-lautriche-anterieure-et-le-rhin-superieur-a-lere-pre-nationale.html

- Fragmentation politique et dualisme Haute/Basse-Alsace avant 1648 : https://publication-theses.unistra.fr/public/theses_doctorat/2016/Maillard_Georges-Frederic_2016_ED101.pdf)

- Histoire du Territoire de Belfort (conquête 1636, confirmation 1648) : https://www.territoiredebelfort.fr/histoire-du-territoire-de-belfort

- Fin de la Décapole et statut de Colmar après 1648 : https://books.openedition.org/pus/8534?lang=en

- Grand-Bailliage d'Alsace (Landvogtei de Haguenau) : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand-Bailliage_d%27Alsace)

- Rôle du Conseil Souverain d'Alsace et privilèges de Strasbourg : https://books.openedition.org/pur/128214?lang=en

- Annexion de Strasbourg (1681) et Politique des Réunions : https://shs.cairn.info/louvois--9791021007154-page-351?lang=fr

- Capitulation de Strasbourg (1681) : concessions religieuses(https://www.bas-rhin.gouv.fr/contenu/telechargement/45544/293740/file/CP+STrasbourg+1681.pdf)

- Statut de Mulhouse et son alliance avec la Suisse (jusqu'en 1798) : https://books.openedition.org/pumi/34731?lang=en

- Mulhouse et la Suisse : 500 ans d'histoire commune : https://www.espaces-transfrontaliers.org/mulhouse-et-la-suisse-500-ans-dhistoire-commune/

- Histoire et architecture de Riquewihr (acquisition par Wurtemberg 1324) : https://riquewihr.fr/fr/rb/724609/histoire-et-architecture

- Introduction de la Réforme à Montbéliard et Wurtemberg (1534) : https://empireromaineuropeen.over-blog.org/2015/02/histoire-du-comte-de-la-principaute-de-montbeliard-grafschaft-mompelgard-furstentum-mompelgard.html

- Succession et administration de la Principauté de Montbéliard : https://francearchives.gouv.fr/fr/authorityrecord/FRAN_NP_051803)

- Fiefs du Duc de Wurtemberg : redevances et nominations : https://portail-archives.doubs.fr/media/a4f65f5c-2056-4e71-a5ff-a1c7bbe943f5.pdf

- Le Simultaneum en Alsace : coexistence religieuse après 1648 : https://museeprotestant.org/notice/le-simultaneum/

- Églises mixtes et coexistence confessionnelle en Alsace : https://books.openedition.org/pur/157652?lang=en

- Carte de la principauté de Montbéliard (1616) et Riquewihr : https://www.landesarchiv-bw.de/de/themen/praesentationen---themenzugaenge/76603

- Institutions judiciaires dans la Province d'Alsace (1657-1790) : https://genealogiealsace.wordpress.com/2021/08/11/les-seigneuries-alsaciennes/

- Clauses du Traité de Westphalie (Paix chrétienne, amnistie, Palatinat) : https://mjp.univ-perp-fr/traites/1648westphalie.htm