The Peace of Westphalia: The End of an Endless War

By the mid-seventeenth century, Europe was exhausted.

For thirty years, the continent had been ravaged by a conflict of unprecedented scale — the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648).

What had begun as a religious quarrel between Catholic and Protestant princes of the Holy Roman Empire had quickly turned into a political war, pitting the great powers of the age against one another: the Habsburgs of Austria and Spain on one side, and France and Sweden on the other.

The countryside lay in ruins, villages were burned to the ground, famine spread everywhere.

In some parts of Germany, the population had been reduced by half.

There was nothing spiritual left in this war — it had become a battle for the survival of states.

By 1643, after three decades of devastation, the warring powers finally agreed to open negotiations.

Five years later, these talks would lead to the signing of the Treaties of Westphalia — a turning point in European history.

The Westphalia Negotiations in Münster and Osnabrück

The talks began in 1644 in two Westphalian towns, in the heart of present-day Germany:

- Münster, a Catholic city, hosted the delegations of France and Spain;

- Osnabrück, a Protestant city, received those of Sweden and the Protestant princes of the Holy Roman Empire.

This geographical division still symbolised the religious fracture that split the continent.

Between the two cities — barely fifty kilometres apart — envoys exchanged letters carried back and forth by horse messengers.

![Münster Historisches Rathaus. Photo © Dietmar Rabich - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons Münster Historisches Rathaus. Photo © Dietmar Rabich - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Munster-Historisches-Rathaus.-Photo-©-Dietmar-Rabich-licence-CC-BY-SA-4.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

Historic Town Hall of Münster, photo © Dietmar Rabich - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons

The discussions would last for over four years, punctuated by endless protocol disputes, disagreements over titles, and fierce debates about the rank of ambassadors.

Yet despite these obstacles, the Westphalian Congress marked a turning point: for the first time, European powers sought to end a conflict through multilateral diplomacy rather than by the sword.

The Treaties of Westphalia thus ushered in a new era — the birth of modern diplomacy.

The Peace of Westphalia: Three Treaties for Two Wars

On 24 October 1648, peace was finally signed.

But contrary to what one might think, it was not a single document.

The Peace of Westphalia was, in fact, a collection of several treaties concluded simultaneously.

Proclamation of the Peace of Westphalia in Münster

1. The Treaty of Münster (France–Empire)

Brought an end to the Thirty Years’ War between France and the Holy Roman Empire.

France gained several strategic territories, notably in Alsace.

2. The Treaty of Osnabrück (Sweden–Empire)

Granted Sweden control of Western Pomerania, Bremen, and Verden,

making it a dominant power in the Baltic Sea.

3. The Treaty of Münster (Spain–Dutch Republic)

Ended the Eighty Years’ War and recognised the independence of the Dutch Republic — today’s Netherlands.

These agreements profoundly redrew the map of Europe.

They also marked the end of the Habsburgs’ imperial dream: the Holy Roman Empire survived, but weakened, fragmented, and without a strong central authority.

The Core Principles of the Peace of Westphalia

The Treaties of Westphalia were not merely territorial compromises.

They laid the foundations of the modern international order, often referred to as the “Westphalian system.”

The negotiations of the treaties

1. The Sovereignty of States

Each prince or nation became master of its internal affairs, free from external interference.

It was a revolution in a world where emperors, popes and religious alliances still claimed the right to intervene in others’ business.

2. Equality Between Powers

Whether France or a small German principality, each political entity was recognised as legally equal.

This marked the birth of the sovereign nation-state.

3. Non-Interference

A country could no longer invoke religion as a pretext to invade or impose authority on another.

This principle — often ignored in later centuries — remains a cornerstone of international law.

4. Religious Tolerance

The treaties reaffirmed the principle of cuius regio, eius religio — whose realm, his religion — but also guaranteed rights for religious minorities.

Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists could now coexist legally within the Holy Roman Empire.

In short, the Peace of Westphalia ended the religious wars and laid the foundations of a political order based on coexistence and diplomacy rather than faith and force.

Strasbourg Cathedral © French Moments

The Political Consequences of the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia completely reshaped the European balance of power.

- France emerged stronger than ever: it gained (part of) Alsace, as well as the bishoprics of Metz, Toul and Verdun, and established itself as the leading power on the continent.

- Sweden consolidated its control over the Baltic Sea.

- The Dutch Republic became an independent and prosperous state.

- Spain began its long decline.

- The Holy Roman Empire remained fragmented — with more than 300 states, principalities, bishoprics and free cities retaining wide autonomy.

- And Switzerland saw its independence officially recognised.

Thus, Europe moved from the dream of imperial unity to a concert of sovereign states — a model that would define international relations until the twentieth century.

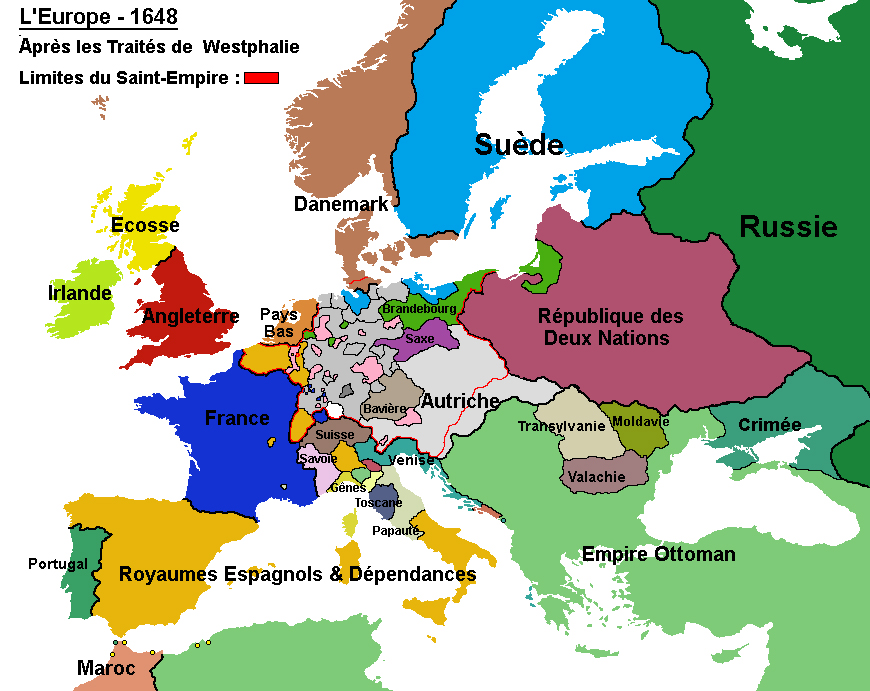

Map: Europe after 1648 by Helio74100 - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Alsace and the Peace of Westphalia: A Change of Destiny

Among the many regions affected by the Peace of Westphalia, Alsace occupied a special place.

1. Before 1648: A Habsburg Mosaic

Before the treaties, much of Alsace belonged to the Austrian Habsburgs.

But the territory was far from unified:

- The Sundgau (including Belfort and Ensisheim) formed the Austrian core in the south.

- The Décapole (ten cities including Colmar, Sélestat and Obernai) fiercely guarded their autonomy.

- Strasbourg was a Free Imperial City, independent of any external rule.

This diversity reflected the complexity of the Holy Roman Empire — a political, linguistic and religious patchwork.

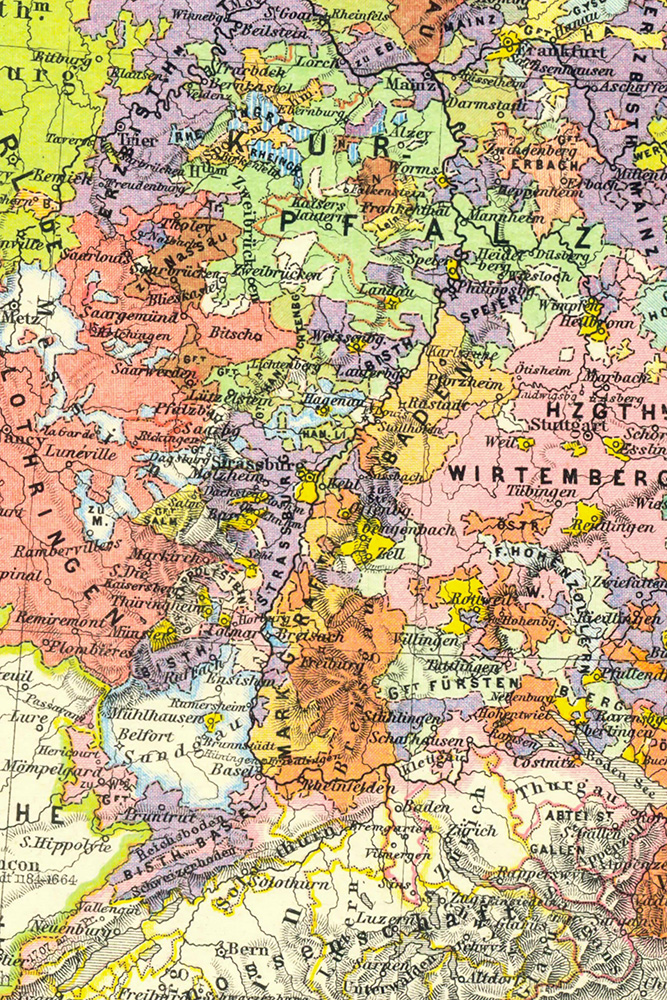

Map: The territorial puzzle of the Upper Rhine region, including Alsace

2. 1648: France Steps In

The Treaty of Münster granted France the Austrian possessions in Upper Alsace, along with sovereign rights over several Imperial cities.

Yet the situation remained ambiguous: France now exercised authority, but Imperial law still applied.

One might say that Alsace became French “in theory,” but remained German “in practice.”

This ambiguity — typical of seventeenth-century diplomacy — allowed for a peaceful but gradual transition.

From the Peace of Westphalia to the Annexation of Strasbourg

After 1648, the kings of France gradually tightened their hold on the region.

Under Louis XIV, the so-called policy of réunions aimed to formally attach to the crown all territories to which France laid claim.

- 1673: Colmar and Haguenau came under French control.

- 1679 (Treaty of Nijmegen): France obtained formal confirmation of its rights over Alsace.

- 1681: Strasbourg — until then a Free Imperial City — was annexed without a single battle.

The King entered the cathedral in solemn procession, promising to respect the city’s traditional liberties.

Only Mulhouse escaped this movement: it remained an independent republic, allied with Switzerland, until it voluntarily joined France in 1798.

Thus, in less than half a century, Alsace evolved from an Imperial mosaic into a French province, while still preserving its linguistic and religious identity.

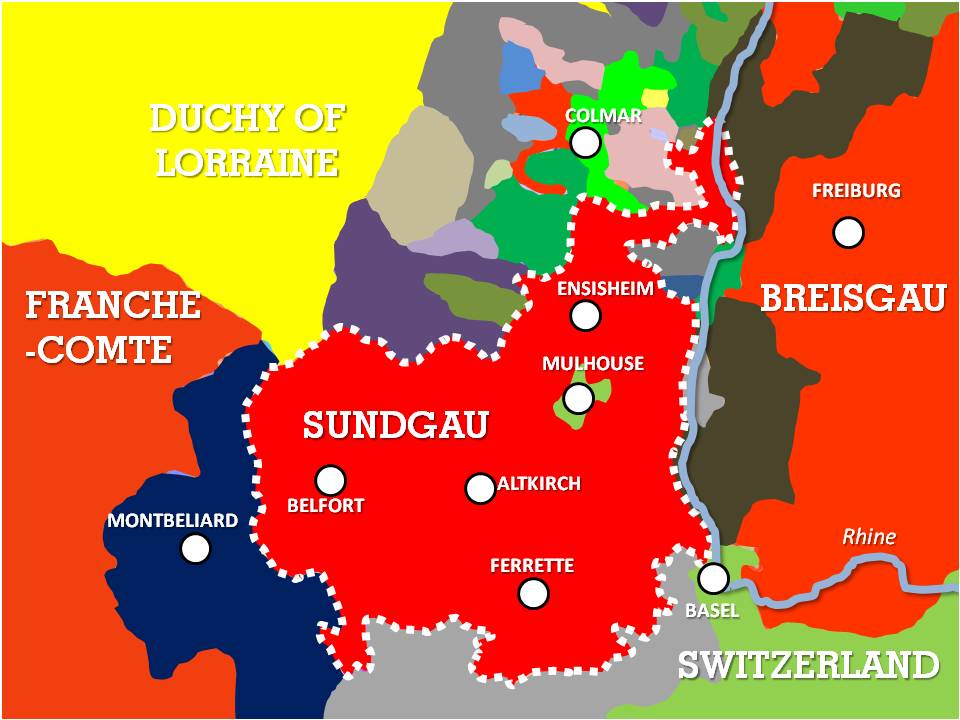

Map: The Sundgau, heart of the Habsburg possessions in Alsace © French Moments

The Legacy of the Peace of Westphalia in Alsace and Europe

The Peace of Westphalia left an enduring mark on European history.

It ended more than a century of religious wars and established a new equilibrium based on diplomacy, negotiation, and the recognition of sovereign states.

For Alsace, this peace marked the beginning of a unique Franco-German story:

- French by its crown,

- Germanic by its language and culture,

- European by its role as a bridge between two worlds.

Even today, the so-called Westphalian system continues to inspire modern international law, while Alsace, in its own way, still embodies the very spirit of compromise — a coexistence of identities, languages, and legacies.

The Regency Palace in Ensisheim © French Moments

Conclusion

The Treaties of Westphalia were not merely the end of a war — they were the beginning of a new Europe.

An Europe built on diplomacy rather than conquest, on sovereignty rather than submission.

And for Alsace, they marked the start of a singular journey — that of a borderland which would one day become a symbol of unity and peace.

Want to Read More?

A few related blog articles you might enjoy: