Lyon History shows the rich heritage of France’s second largest city which has very much influenced the way the city looks today. From the Roman era to the 20th century, through the Renaissance era and the French revolution, it has been quite a turbulent story.

Lugdunum: the Roman origins of Lyon

It is believed that the place where Lyon stands nowadays has been occupied for the last 40,000 years. Archeologists have found evidence suggesting there were humans living in the area since that time.

Commercial activities in the area may have started slowly 2,800 years ago. These activities remained low key until the Romans arrived however it shows that the Roman city was not created from nothing! Agriculture and handicrafts were developing in the area, permitting populations to settle themselves there from the Neolithic era. During the Stone Ages (from the 6th century BC), the area appears to have been a commercial platform for wine between Mediterranean cities and Northern France. That fact was proved by the remains found in the Vaise district by archeologists.

However, we can talk of Lyon’s birth as a city with the arrival of the Romans during the 1st century BC. Around 120 BC, the Romans wanted to conquer the whole of Gaul. They soon understood how important the Rhône river and valley were for this purpose. Indeed, they realised the area could be used as an axis for spreading communication, trade and culture. The Romans conquered the Rhône valley from the Mediterranean sea to Vienne, located 30 kilometres South of Lyon, in 121 BC. Under Julius Caesar’s command, they then defeated the local people, called Allobroges, during the Gaul war and created the latin colony Julia Vienna in Vienne, around 50 BC.

![Bust of Lucius Munatius Plancus, from the 1st Century AD © Photo: Rama, licence [Cc-by-sa-2.0-fr], from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Bust_of_Plancus_IMG_9753.jpg)

In 43 BC, one year after Julius Caesar’s assassination, the Roman regional chief Lucius Munatius Plancus founded a new colony called Lugdunum on what is today called Fourvière Hill. The name of the colony comes from the Gaulish words “Lug” and “Duno”. “Lug” means “light”, but this is also the name of one of the most important Gallic gods. “Duno”, the latin version of which is “Dunum”, means “hill”. Consequently, Lugdunum is the Hill of Light, or the Hill of the God Lug. Lucius Munatius Plancus had power over the city in every single aspect of Lugdunum’s life.

Details about the first years of the colony remain quite unknown today. However, what is known is that Lugdunum soon gained strong regional importance. In 27 BC, Gaul was divided into three provinces by Augustus and his minister Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. The new provinces were Gallia Lugdunensis (which we know today as the area from Lyon to Brittany), Gallia Aquitania (the Western part of Gaul) and Gallia Belgica (the Northern part). Lugdunum became the capital city of Gallia Lugdunensis. It was also the headquarters of Roman imperial power over the three newly created provinces. Consequently, Lugdunum was also known as “the Three Gauls’ Capital” (“la Capitale des Trois Gaules”).

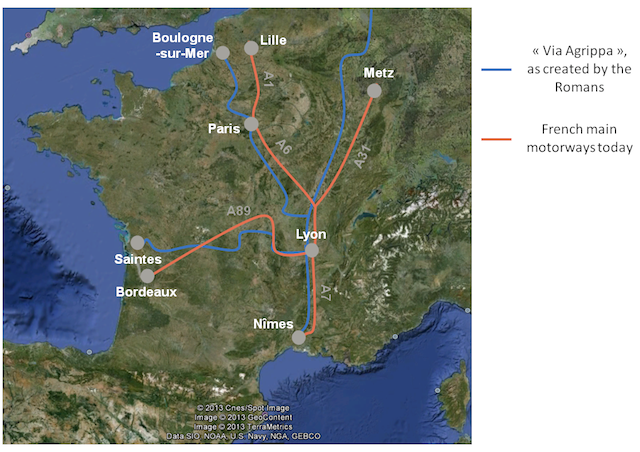

Lugdunum became the administrative, commercial and cultural centre of the Gauls. The network of Roman roads through the Gauls was built to link various cities to Lugdunum. They are known as “Via Agrippa”.

- The first crossed Gaul from West to East, from Lugdunum to the Atlantic Ocean, reaching the city of Mediolanum Santonum, nowadays known as Saintes.

- The second reached the English Channel and was known as “Ocean Via Agrippa”. Starting from Lugdunum, it then crossed cities known today as Châlon-sur-Saône, Beauvais and Amiens, before finishing its journey in Boulogne-sur-Mer.

- The third went to the North-East of Gaul, to a colony called Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, now known as the German city of Cologne. It crossed Andemantunnum (Langres), and Divodurum Mediomatricorum (Metz).

- Finally, the fourth joined Gallia Narbonensis, to Gaul’s South-East. It joined some of what are considered today as the French cities with the biggest Roman legacy: Vienne, Valence, Avignon and Arles, for example.

It is interesting to compare those routes to today’s main roads which start in Lyon. They follow almost the same patterns!

Lugdunum quickly became a typical Roman city. In less than thirty years, the most important facilities were built. The “Sanctuaire fédéral des Trois Gaules” (Three Gauls’ federal sanctuary) was built on what we know today as Croix-Rousse hill. It was a political building, where sixty chiefs from all over Gaul met once a year during the “Three Gauls Council”. The goal of this meeting was to represent the interests of Gauls to the Roman ‘government’. To some extent, the Three Gauls Council can be considered the first French parliament! The sanctuary was massive and one of the most important buildings in Lyon during the Roman era. It was dedicated to Rome and to the emperor as the writing “ROM-ET-AUG” (“Romae et Augusto” – To Rome and to Augustus) suggests. However, all we know about this building today comes from texts that were discovered by archeologists, since the building was destroyed. Coins representing the hostel of the sanctuary were also found.

An amphitheatre used to stand next to the sanctuary. It hosted some of the meetings that were part of the Three Gauls Council. Unlike the sanctuary itself, some parts of the amphitheatre remained and were discovered one after another from the early 19th century to the 1970s. It was first built in 19AD but it was extended in the 2nd century. The amphitheatre was the biggest in Gaul, being more than 140 metres long and 115 metres wide, according the archeologists. It could host more than 20,000 people. Gladiator fights, as well as some Christian executions such as St. Blandina’s in 177, took place in this huge building.

As in most of the Roman cities, there was a forum in Lugdunum. It was the main place in the city, where people could meet and where the main political, administrative and religious buildings stood. According to the archeologists’ work, Lugdunum’s forum used to stand where Fourvière basilica is nowadays located. It might even have given its name of the hill: Fourvière comes from “Forum vetus”, which means “Old forum”. According to historians, the forum appears to have collapsed during the 9th century. Some of the remaining stones were used to build Lyon Cathedral Saint-Jean.

The life of Lugdunum was organised around the forum. Consequently, most of the Roman remains were found on Fourvière Hill. In particular, many commercial vestiges (coins, vases…) have been discovered but also several bigger buildings. The most emblematic of them are the Fourvière Roman theatre and the Odeon. Built between 15BC and the 2nd century AD, they have remained almost intact. They were discovered and cleared in the middle of the 19th century. They are still useful nowadays. For example, the “Nuits de Fourvière” (Fourvière Nights) festival takes place there every summer. This live performing arts festival has become one of summer’s main events in Lyon, with well-known artists from all over the World performing.

With all these roads and political and cultural monuments, Lugdunum soon became the most important town in Gaul and one of the major cities throughout the Roman Empire. It was a big commercial platform, especially because of the two rivers located at the bottom of Fourvière Hill: the Saône and the Rhône. The rivers were used as a means of communication between Lugdunum and other places in the Roman Empire. The Romans built military and commercial warehouses along the two rivers. What we know today as Lyon Presqu’île was then called “canabae”, which means cellar or warehouse. This word was used in many Roman cities, to identify the place where many warehouses are established. The peninsula between the Rhône and the Saône started to gain strategic importance for the Romans. Archaeologists found much evidences of the Roman presence throughout the Presqu’île. Sixty mosaics and many other ancient objects were unearthed around the peninsula, bearing witness to the commercial weight of this area of Lugdunum.

The city was at its height during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. However, from the end of the 2nd century, it started to decline, just like the Roman Empire itself. The political and religious situation was unstable. Lugdunum especially faced a troubled religious situation, with many Christians being executed at the end of the 2nd century. The city lost its “Gauls capital” ranking in 297 AD, being replaced by Trier, a city now located in Germany.

Economically speaking, the situation became very complicated at the beginning of the 4th century. The city’s administrative power struggled to maintain the public institutions of Lugdunum, such as the aqueducts. The population, located at the top of Fourvière Hill, could not be provided with water. Consequently, people had to go down the hill: the “Vieux-Lyon” area then started to be populated, since it was closer to the rivers. According to historians, those important movements of population gave birth, for instance, to what we know today as Rue Saint-Jean (St. John street).

The city then became more vulnerable to barbarians’ invasions, especially during the 5th century. Neither the “municipality”, nor the Empire could help Lugdunum’s people to defend themselves. In the middle of the 5th century, the Burgundians reached the Lyon era and conquered it easily. Finally, in 476, the Roman Empire collapsed: meaning the end of the Roman era of Lugdunum.

After having been one of the most important city of the Roman empire for three centuries, Lyon struggled to regain its ranking.

Lyon during the Middle Ages

However, after having ruled the city for less than one century, the Burgundians were defeated by the Franks in Lugdunum in 534. The consequences on the city’s influence were terrible, since the Franks decided to transfer the political power over the region to the town of Châlon-sur-Saône located around 100 kilometres to the north. Since then, and for centuries, Lugdunum’s power was mainly religious. Until the 11th century, the Bishop was the most powerful figure in the city, having power over northern dioceses like Mâcon and Châlon-sur-Saône.

In 843, Charlemagne’s grandsons Lothar I and Charles the Bold inherited one part of the town each. Charles got the western part, whereas Lothar got the eastern part. However, according to the Bishop’s, this division was only fictional… In fact, Lothar and Charles had no power over their respective areas. Only the bishop had!

This ecclesiastical domination remained for centuries. It was even greater from 1079, when Lyon’s bishop got the “Gauls’ primate” position. This title was first given to Bishop Gébuin by Pope Gregory VII. Consequently, the powers of Lyon’s bishop could be felt right up to Rouen’s diocese in Normandy!

Lyon developed relatively slowly compared to other cities in France. The city was not really involved in commercial activities and was only developing because of the activities of the Clergy. At that time some of Lyon’s main religious buildings, such as St. John Cathedral an St. Martin d’Ainay Abbey were constructed.

The city had to wait until the 13th century to gain some economic importance on a grand scale. The bourgeois from Lyon started to confront the religious hierarchy: they wanted to be more independent and to be able to run their own businesses. One of their main claims was to become the owners of their houses. Indeed, at that time, the whole of the town’s land belonged to the Church! The 13th Century was marked by riots and fights between three groups: the Clergy, the nobles and the bourgeois. Finally, the bourgeois achieved some rights. In 1267, they were able to create a political council.

Meanwhile, taking advantage of these divisions, the King of France succeeded in imposing his power over Lyon. The town was historically part of the Holy Roman Empire, even if the bishops actually ran the city for centuries. In 1311, King Phillip IV of France eventually seized power over the city, thanks to the problems confronted by the Clergy and the lack of interest by Emperor Henry VII in Lyon.

By the end of the Middle Ages the town was growing, though diminished compared to its former importance at the peak of the Roman Empire. The bourgeois became more important in the city’s administration. In 1320 a Charter called “Saupaudine” was signed, creating a permanent council of 12 people elected by the most important bourgeois of Lyon. The economic importance of the town still remained local. The city had to face the demons of the end of the Middle Ages: about twelve plague epidemics, floods, famines, armed groups spreading terror…

To sum up, the Middle Ages were definitely tumultuous for Lyon! The Renaissance, however, marked a real move forward for the town when it entered modernity.

Lyon from the Renaissance to the 18th Century

At the beginning of the Renaissance, the city was not as spread out as it is today. Lyon people mainly lived in two areas: the right bank of the Saône was a major area and has become what we know today as Lyon Old Town. People also started to live in the Presqu’île, especially around the Via Mercatoria: the “Rue Mercière” (Merchant street). This was the commercial centre of Lyon. While the city was not really spreading out at the time, it became denser. The population increased exponentially: from 25,000 inhabitants around 1450, there were 35,000 people living in Lyon in 1520 and twice this figure thirty years later!

This population growth can be explained by the economic growth. From the end of the fifteenth century, Lyon again became an important commercial hub, which had not happened for more than a thousand years. Being fully part of the French kingdom, the city more easily became a major trading place. Many different types of goods were traded in Lyon at that time: spices, knives, weapons, silk sheets… Merchants and bankers from Italy settled in Lyon and played an important part in the growth of the city.

They started building beautiful houses in the Saint-Jean and Saint-Paul areas. Some of them, such as the Gadagne family and their beautiful and unusual houses, are still famous nowadays. They have become museums, one being a puppet museum, the other the Lyon History Museum. Lyon was also a major place in Europe for printing, which was created in its modern form by Gutenberg in the 1450s. From the end of the 15th century to the beginning of the 16th, publishers moved into Lyon and set up businesses. In 1519 the Great Company of Lyon’s Booksellers was created. The Printing Museum of Lyon, established in 1964 in Lyon Presqu’île, is situated in the “Hôtel de la Couronne”. In the 16th century, the hotel belonged to one of those Italian merchants who contributed to Lyon becoming a major influence in Europe.

Even though the city was doing better during the Middle Ages, all the problems were not solved. Lyon still had to face social troubles. In April 1529 the “Grande Rebeyne” (the Great Riot) happened. For a few months, wheat prices had been increasing, because of bad weather conditions. On the 25th April, some wealthy people’s houses were damaged and destroyed in several areas of the town, such as the Terreaux district and the Croix-Rousse hill. The main social troubles arose out of the birth of a Protestant community in Lyon, in the mid-16th century. French King Henry II was deeply Catholic, and he severely repressed Protestants. When he died, Protestants felt freer and wanted to take a more prominent role in the city’s life. Several bloody riots occurred, with Catholics facing Protestants. The saddest example of religious violence happened in 1572. After Saint-Barthélémy night, when thousands of Protestants were killed by Catholics, 700 Protestants from Lyon were drowned by Catholics in the Saône river. Those religious troubles only stopped at the end of the 16th century, when Henry IV of France increased his power over Lyon to limit religious riots.

For two centuries, Lyon was then submissive to the French King’s authority. The merchants had less power at the beginning of the 17th century, deferring to the King’s representatives. However, Lyon continued to be a very important commercial region, in particular because of the silk industry. The “Loge du Change” (Exchange Lodge) was established in the St Paul district to conduct financial transactions. The silk trade continued to grow. Three years before the French Revolution, there were almost 15,000 weaving looms in the Lyon area! Consequently, at the end of the 18th century, Lyon had the highest workers’ population. The first workers’ riots took place in 1786, led by the “canuts” (Lyon’s silk workers) and was severely repressed.

Over time, the city centre started to shift from the right bank of the Saône to the Presqu’île area, between the Rhône and the Saône. A good example of this movement was the construction of great buildings that have given the city its current shape. The Hôtel-Dieu, as we know it today, was built on the right bank of the Rhône throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. It encouraged famous and skilled doctors, making Lyon a main centre for health research. The wonderful facade of the Hôtel-Dieu was constructed during the second half of the 18th century, with the famous dome being finished in 1764.

On the Presqu’île again, the Palais Saint-Pierre (St. Peter Palace) was opened in 1689. At that time, it used to be a convent where the “Dames de Saint-Pierre” (St. Peter’s ladies) lived. The Town Hall was also built in this period, at Place des Terreaux (Terreaux Square). The history of this building is troubled: two years after its opening, it was destroyed by fire. The famous architect Jules-Hardouin-Mansart redesigned the building, which was substantially changed from the original plans by Simon Maupin.

Lyon during the French Revolution

Lyon entered the French Revolution times divided. Various different types of people lived in the town and wanted their own interests to be represented during the “Etats Généraux” (General Estates), launched by King Louis XVI at the beginning of 1789. Conservatives (Clergy and Gentry) confronted the liberal bourgeoisie and revolutionary workers.

Early summer in 1789 witnessed a rise in the social tensions. The working classes wanted swift and important social changes. The liberal bourgeoisie, even if in favour of a new social situation, wanted things to change more gradually. People from the Third Estate started to demonstrate in late June 1789, against taxes on imported products. On July 14th, while Parisians were storming the Bastille, people from Lyon started doing the same with the Castle of Pierre Scize, an old fortress built in the 10th century over the Saône river. During the “Grande Peur” in Summer 1789 (Great Fear), much plundering took place in Lyon, against wealthy people’s houses, either from the bourgeoisie or from the Gentry.

It was decided to harshly repress these riots. The situation remained troubled, in spite of the arrival of a new municipal council. While working class representatives, such as Marie Joseph Chalier, asked for significant and faster reforms, the conservatives wanted to seize power back, without success. 1790, 1791 and 1792 were bad years for the economy and the tensions continued to rise. The political situation remained blocked, despite the first municipal elections taking place in 1791. In late summer 1792 the “septembrisades lyonnaises” happened: those riots led to twelve people being murdered.

1793 was the most troubled year in Lyon during the French Revolution and perhaps in the town’s history. The National Convention wanted to track people who were against the Revolution. These were the terror times: many moderate politicians were arrested. Jacobins gained a majority in the municipal council. Being deeply revolutionary, they took several extreme decisions that led them to be unpopular to Lyon’s population. The Girondists, being more moderate than the Jacobins, seized power in the municipal council notwithstanding that they were considered illegal by the National Convention! The harshest part of the Terror in Lyon commenced during this time. After facing a siege for two month between August and October 1793, Lyon’s army was defeated by the revolutionary forces from Paris. More than 1,600 people from Lyon were sentenced to death for counter-revolutionary behaviour. The last years of the 18th century were terrible times for the town and its people, who were shocked by the events of the Revolution.

Lyon in the 19th Century

During the first two French empires (First Empire: Napoleon I, 1803-1815; Second Empire: Napoleon III, 1852-1870), Lyon undertook major reconstruction and was modernised. The already populated areas were markedly changed. Several buildings that suffered damages during the French Revolution were rebuilt. Then, the city’s chief-architect Tony Desjardins and chief-engineer Gustave Bonnet “copied” Haussmann’s plans in Paris. The Presqu’île was totally refurbished. In those days, the main streets from the district were built as what we know today as the Rue de la République and Rue du Président Edouard Herriot.

Also, many emblematic buildings of today’s Lyon were built such as the “Palais du Commerce” (Trading Palace). The Parc de la Tête-d’Or (Golden-Head Park) was also created, so was the Perrache railway station. Meanwhile, the city was extending to new areas. Bridges were built over the Saône and the Rhône rivers. The Eastern parts of the town (Brotteaux and Guillotière district), such as the Vaise area to the west, started to be populated.

![Jardin Botanique Lyon © Simlaurent licence [CC BY-SA 3.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Jardin-Botanique-Lyon-©-Simlaurent-licence-CC-BY-SA-3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

As for the social situation, the 19th century in Lyon was marked by the development of the working class, especially in the silk industry. In the 1850s, more than 90,000 people were silk workers, also known as “Canuts”. Most of them lived in Croix-Rousse Hill, which was nicknamed as the “Working Hill”, whereas Fourvière Hill’s nickname was the “Praying Hill”. Despite the global growth of the silk industry, the social situation was hard for workers. Two Canut riots took place in Lyon, in 1831 and 1834. They are often considered as the first riots linked to industrialisation and inspired many philosophers and writers in Europe such as Stendhal and Charles Fourier. However, they were harshly repressed and many Canuts and policemen died during the riots. Those events led to the creation of the Canuts’ motto: “Vivre en travaillant, ou mourir en combattant” (Live while working or die while fighting). The social situation in Lyon remained troubled at the end of the Second Empire.

At the beginning of the 19th century one of the most emblematic figures of Lyon, the Guignol puppet, was invented by Laurent Mourguet. This puppet theatre was initially mainly about improvisation: Mourguet did not like to write plots and enjoyed performing various situations. To many people’s eyes at that time, Guignol played the part of the working class’ spokesman. Nowadays, this puppet show remains popular in the Lyon area. It even inspired one of the most famous French TV programmes: the satirical puppet show called “Les Guignols de l’Info” (News Guignols).

Lyon during the 20th Century

Lyon entered the 20th century a very dynamic city. In the 1890s, the Lumières Brothers invented the cinema, making the city an important place for innovation and for culture. While the traditional textile industry, especially the silk industry, slowly started to decline, new economic areas became important. The chemical sector started to become important and helped to modernise the textile industry. Big companies such as Rhodiaceta and Rhône-Poulenc became the main firms in the Lyon area. Meanwhile, medicines and vaccines have developed in Lyon’s research centres. The automobile industry was also important in the first half of the 20th century, with companies such as Voisin and Berliet, which would become Renault Vehicules Industry, being created in Lyon.

The first half of the 20th century in Lyon is also symbolised by the figure of Edouard Herriot. He was the mayor of the town from 1905 to 1940 and from 1945 to 1957. He is still important in the eyes of the Lyon people, with many streets, schools and facilities in the town being named “Edouard-Herriot”. While he was mayor, he refurbished many parts of the city and caused many buildings to be built. His favourite architect was Tony Garnier, who designed the Hall of Lyon (nowadays known as Tony Garnier Hall), the biggest hospital in the town (named “Hôpital Edouard-Herriot” after the emblematic mayor’s death) and the biggest stadium in Lyon (Stade de Gerland). Herriot and Garnier also continued the extension of the town to the west, creating the new “Quartier des Etats-Unis” (United States area).

During the Second World War, Lyon was one of the main cities of the Résistance movement. A civil Résistance movement was born in the city: many young people from Lyon avoided and demonstrated against the “Service du Travail Obligatoire” (Compulsory Working Service) created by Germany during the war. That policy led hundreds of thousands of young French men to be temporarily sent to Germany in order to work in factories. Lyon was even considered as the Capital city of the Résistance, being the town where most of the clandestine newspapers were published. On December, 31st of 1943, the Résistance did something spectacular. The official copy of the newspaper “Le Novelliste”, which was used to support the Nazis’ actions, was replaced by a clandestine one. At first sight, nobody could see the difference, since the format was the same as the original newspaper. However, the writings were totally different, criticising the Nazis and letting people know about the acts of the Résistance.

In peoples’ minds, the Résistance in Lyon is embodied by Jean Moulin. He was a senior civil servant. In 1940, he decided not to follow the official policies of Maréchal Pétain’s official regime and joined Général de Gaulle in the “France Libre” (Free France) movement. He was in charge of unifying the various sections of the inner-Résistance and headed them in the Lyon region. In March 1943, he created the “Conseil National de la Résistance” (Résistance National Council). On June, 21st, he was arrested after a meeting in Caluire-et-Cuire, a Northern suburb of Lyon. He was interrogated and tortured by the Gestapo and died on July 8th while he was on a train to Nancy to face new interrogations.

During the second half of the 20th century, Lyon entered modernity. The parts of the town that suffered damage during the war were refurbished. Lyon’s Old Town was restored, after having almost being deserted by the municipality and having become unhealthy. The French Minister of Culture, André Malraux, played an important part in the process, by ranking the Old Town as a “secteur sauvegardé” (saved area) in 1962. Finally, the UNESCO ranked the Old Town as a World Heritage site in 1998. Lyon’s opera house was modernised in the 1990s by the famous French architect Jean Nouvel. The Rhône banks were also refurbished in the mid-2000s. Pedestrian ways have been created, extending from the Parc-de-la-Tête-d’Or to the Gerland area.

Meanwhile, new areas were being built in the town. The most emblematic of those districts, created during the second half of the 20th century, was the Part-Dieu area. There used to be military barracks there until 1957. Since the 1980s, many offices, apartments and hotels have been built there. Lyon Part-Dieu became the second business district in France, after Paris’ La Défense. In 1975, a huge commercial centre opened: at the time, it was the biggest commercial centre in Europe. In 1983, the Part-Dieu railway station was created. It soon became the biggest station in Lyon with the TGV joining people to Paris in two hours. From the 1980s to the 2000s, the area did not evolve much. However, for a few years, the Part-Dieu district has been changing, with new towers being built. By the end of the decade, the railway station should be renovated, along with the economic development of the area.

English-French vocabulary

(f) for féminin, (m) for masculin, (adj) for adjectives and (v) for verbs

- acqueduct = aqueduc (m)

- ancient = antique (adj)

- Antiquity = Antiquité (f)

- archeologists = archéologues (m)

- bank (for a river) = berge (f) or rive (f)

- Bishop = évêque (m)

- building = bâtiment (m), construction (f)

- central business district = quartier des affaires (m)

- church = église (f)

- coin = pièce (de monnaie) (f)

- colony = colonie (f)

- company = entreprise (f)

- district = quartier (m)

- to embody = incarner (v)

- engineer = ingénieur (m)

- epidemic = épidémie (f)

- flood = inondation (f)

- Gallic = gaulois (adj)

- Gentry = noblesse (f)

- growth = croissance (f)

- handicraft = artisanat (m)

- hill = colline (f)

- to host = accueillir (v)

- King = roi (m)

- knife = couteau (m)

- mayor = maire (m)

- Middle Ages = Moyen-âge (m)

- museum = musée (m)

- network = réseau (m)

- pedestrian = piéton (m or adj)

- plague = peste (f)

- plundering = pillage (m)

- printing = imprimerie (f)

- puppet = marionette (f)

- railway station = gare ferroviaire (f)

- to reach = rejoindre, atteindre (v)

- remains = vestiges (m)

- to repress = réprimer (v)

- rights = droits (m)

- riot = révolte (f)

- Roman era = époque romaine (f)

- Roman road = voie romaine (f)

- to rule = diriger (v)

- to sentence to death = condamner à mort (v)

- silk = soie (f)

- spices = épices (f)

- street = rue (f)

- town = ville (f)

- useful = utile (adj)

- warehouse = entrepot (m)

- weapon = arme (f)

- working class = classe ouvrière (f)

To get more information about Lyon History, you can visit Lyon’s tourism office website.

Thanks for a well written and interesting description of the history of one of my favourite european cities.

Dag Widmark

Sweden

Thank you Dag for your feedback! Lyon is indeed a very beautiful city. 🙂