Colourful, decorative and flowery, the half-timbered houses in Alsace are part of the local landscape and contribute to the image of a region located on the side of France. The warm and welcoming look of the houses is striking, evoking images from a fairy-tale book. Red geraniums, bright as lipstick, gaily dress their façades in well-tended boxes.

The integration of the house in the village

Unlike the houses found in the linear-style villages of neighbouring Lorraine, those of the Alsatian villages are always independent of each other. They never share a common wall; each house serves as a unique entity while still harmonising itself with the whole village. The façade facing the street is the narrowest. In the Sundgau, a small garden separates the house from the road and the entrance door is located on the longest side of the house.

Most Alsatian villages are organised as “heap villages” (in French, “Village-tas”). The houses are gathered around a central square, a place for meeting and exchange, in which an ancient lime tree typically stands. A little stream crosses the village, punctuated by the watermill and the wash house upstream.

The lands and forests surrounding these villages are demarcated by boundary stones and lined with crosses, calvaries or resting benches (in French, “bancs reposoirs”).

Even though the half-timbered house stands out as one of the emblems of Alsace, it would be misleading to believe that it is unique and shared throughout the region. In fact, Alsace contains a variety of house styles depending on the locality and situation. A visit to the Écomusée of Alsace shows the different styles of houses according to the “Alsatian Pays”: Sundgau, vineyards, plain, Vosges, Outre-Forêt…

The winemaker’s house

In the area of Kaysersberg and Ribeauvillé, the villages developed inside ramparts with tortuous narrow streets, front and back overlapping courtyards and multi-storey houses. The villages are either perched at the top of a hillside (Zellenberg), flanked on a hill (Hunawihr) or located on the plain (Bergheim).

Because of narrow streets and a scarcity of land, the winemaker’s house features particular characteristics. Its wine cellar, built from cut stone and half-underground, occupies the central position. The living areas on the upper floors are made from exposed timber frames, often richly decorated. The ceiling of the cellar, without a vault, is often supported by a central pillar. This allows for better heating of the cellar in winter, as a constant temperature and the absence of frost are essential for good wine production.

Cut stone (in French, “pierre de taille”) is often used, particularly on the ground floor, the upper floors being most often half-timbered.

The Renaissance houses owned by well-off tenants in the 16th and 17th centuries often included a corbelling structure, a piece of masonry jutting out of a wall to carry any superincumbent weight, creating extra room for the upper floors.

A Renaissance style displays the sumptuousness of the façade decoration sculpted décor: shop signs, light panels and window frames, corner pillars and bow windows in wood or stone that are placed in the centre of the gable or at the angle of the house. The decoration themes include foliage, human or mythological representations, and typical wine-related artefacts. This decoration serves as a display of the winemaker’s wealth and loudly proclaims his material comfort.

The wood in the building process

With the proximity and abundance of large forests in Alsace (Vosges, Haguenau and Hardt forests), wood has naturally become a first choice raw material for the construction of houses. Easily transportable, wood is resistant to subsidence and earthquakes and is a good insulator, making it ideal for the Alsace climate, which can be quite extreme during winter.

The construction of half-timbered houses in Alsace

A half-timbered house is the work of a carpenter. Only the excavation of the cellar, the foundations and sometimes the ground floor require the intervention of a mason. Nothing is left to chance: the construction of the house must follow stringent rules. Each element of the timber structure must be in harmony – also known as ‘architectonic equilibrium’. The house is formed as a sort of timber carcass (in French, “colombage”) which serves as a solid bone structure.

Screws or nails are never used in the traditional carpentry techniques of Alsace, and the strength of the structure is reinforced by using wooden plugs.

Once the carcass is finished and laid out, the walls are completed by the application of a mortar consisting of mud and straw (in French “torchis” or in Alsatian dialect “Lähme” or “Wickelbodde”). The torchis are applied over palançons (in Alsatian dialect “Flachtwarik”), which are short staves jammed between the posts of the timber-frame wall. The whole set is covered with a lime render which is often white but can also be blue (the colour of the Virgin), red, ochre, green or yellow.

The steeply sloping roof (up to 60 degrees) was designed to prevent snow from collecting and was made of brown or red flat clay tiles in the shape of a beaver’s tail (in Alsatian dialect “Biberschwanz”). Adding to the picturesque edifice, white storks set up their nests on the chimneys in spring.

The symbolic features found in the timber

The respect for architectural principles by carpenters does not prevent including various creative elements, which often have a symbolic meaning.

The Mann

Composed of vertical and slanting beams, the Mann forms two Ks opposing one another. Evoking the silhouette of a man, the shape is a sign of virility and physical force. There are several shapes of Mann: half-Mann, Mann with a head, and Mann at an angle. In the region of Sélestat, a Mann depicting the head of a rooster with its eye can be found, referring to the belief that the rooster – the animal of the sun – repels witches’ spells.

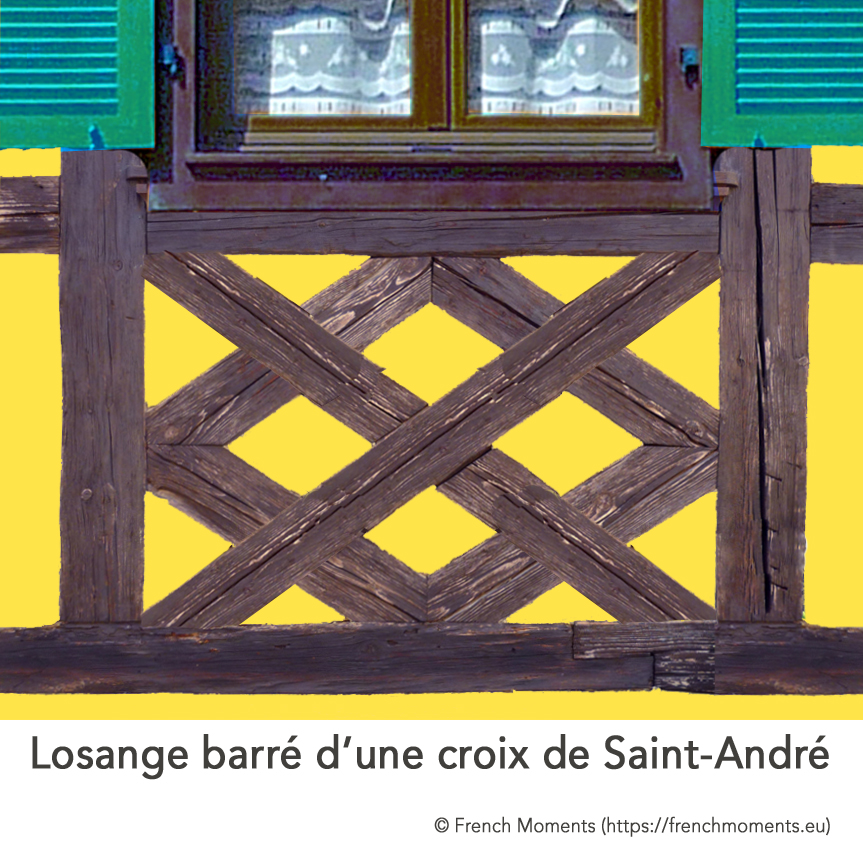

The St. Andrew’s cross (Croix de Saint-André)

Very common in Alsace and Germany, the St Andrews cross forms an X shape found in headlight windows or at the top of gables. It can be seen in the decoration of panels or on the balustrades of balconies. The cross is a sign of multiplication and fecundity for men and animals. When it is doubled, it signifies the union of two beings.

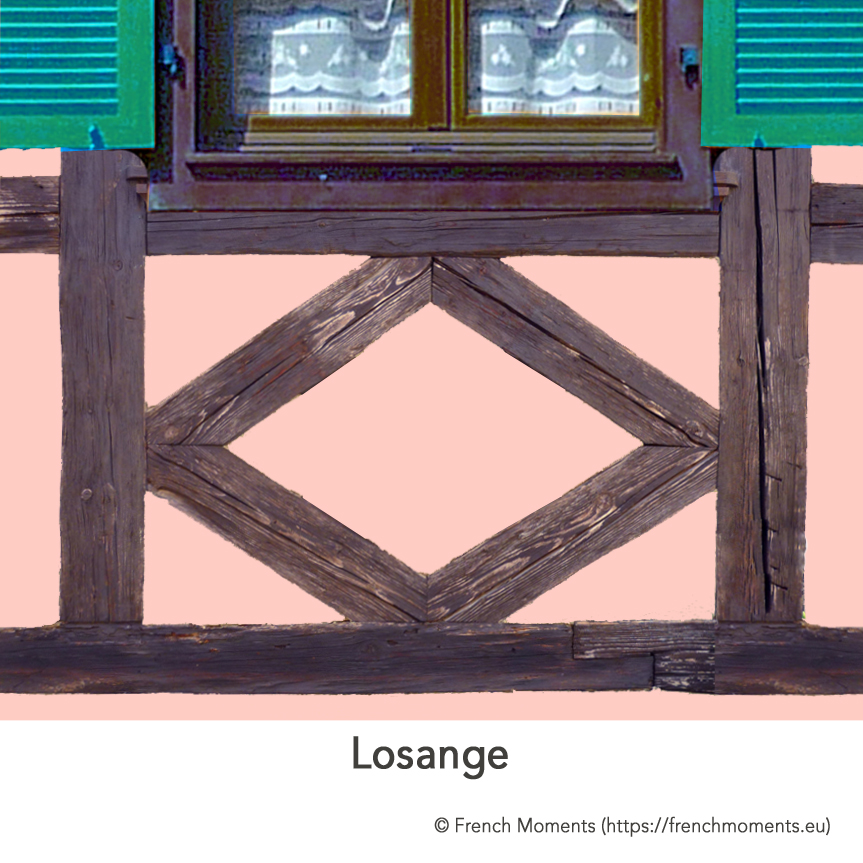

The diamond-shape (Losange)

Also very common in Alsace in headlight window, the diamond shape is the sign of femininity and motherhood.

The combination of the diamond shape and the St. Andrew’s cross is often seen in Alsace, houses, and stables. It signifies multiplication and fecundity, a large family and a significant livestock size.

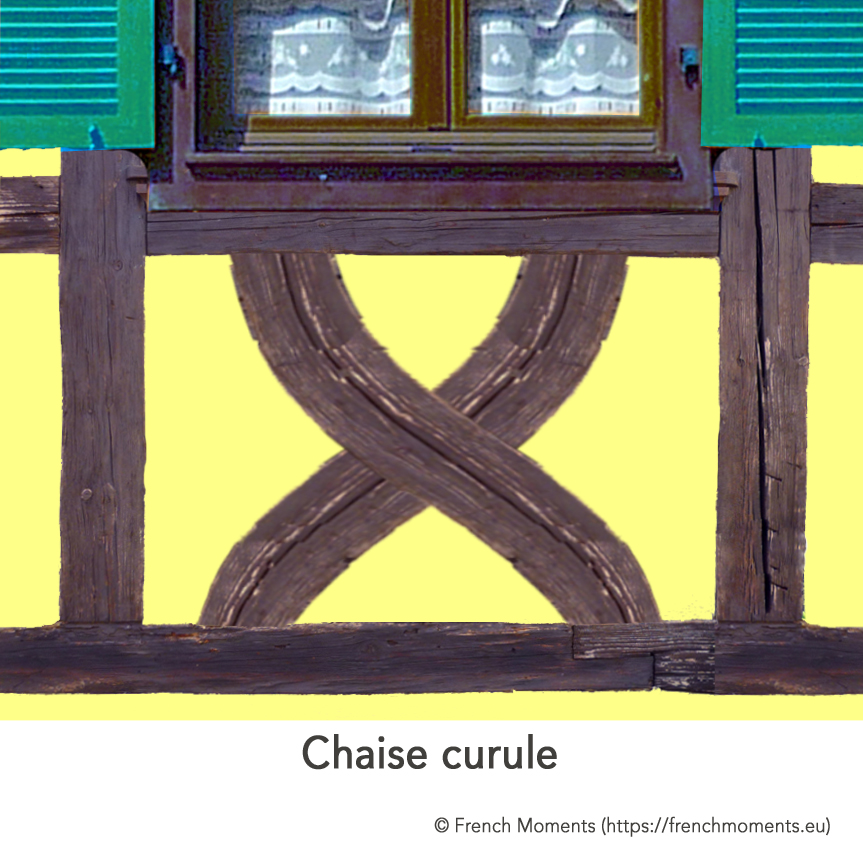

The curule seat (chaise curule)

It comprises the two curved arms of the S, an exaggerated shape of the St. Andrew’s cross, and is often found in headlight windows. However, its significance differs: it refers to the home of a “chief” or an important village character. In Ancient Times, the curule seat was the chair Roman dignitaries were entitled to sit on.

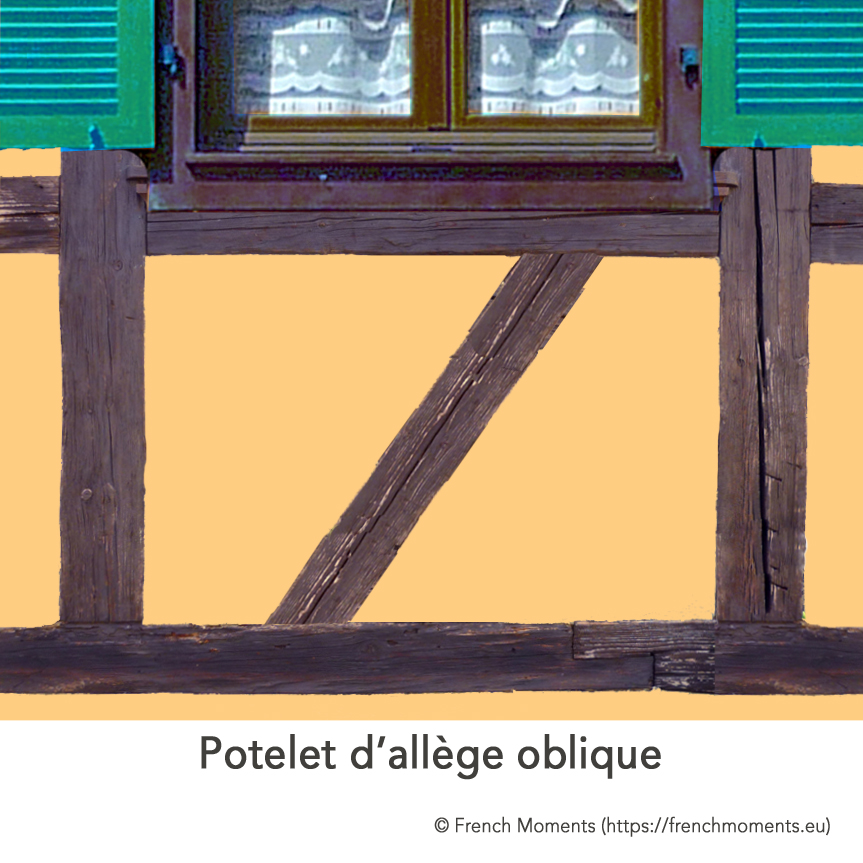

However, several headlight windows feature a simple piece of wood with a vertical beam.

A diagonal

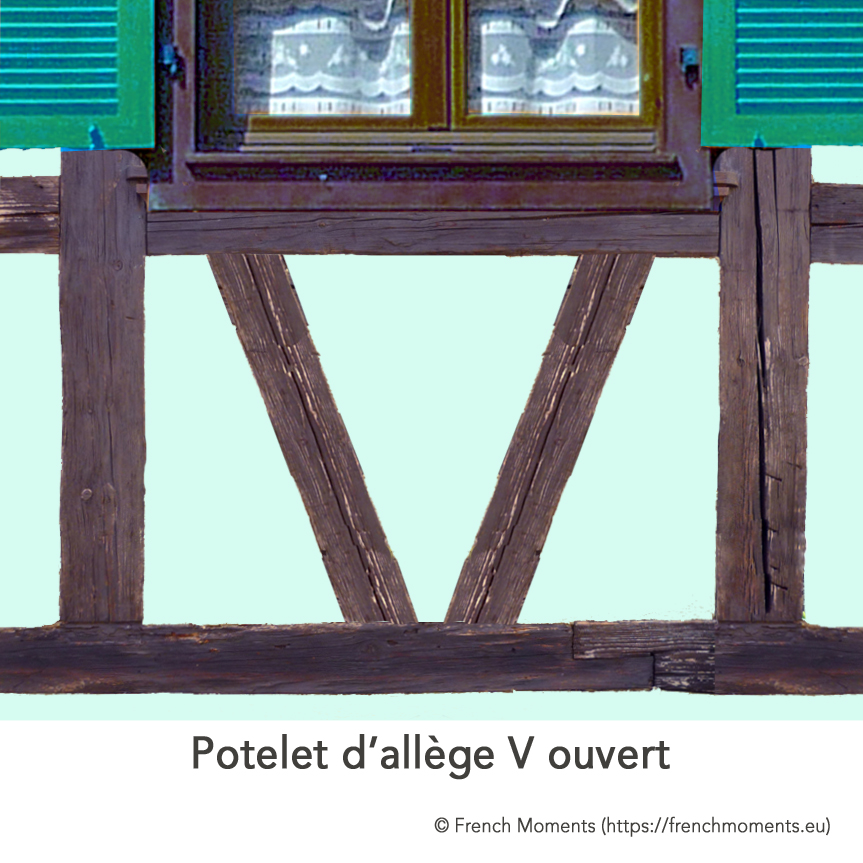

A V

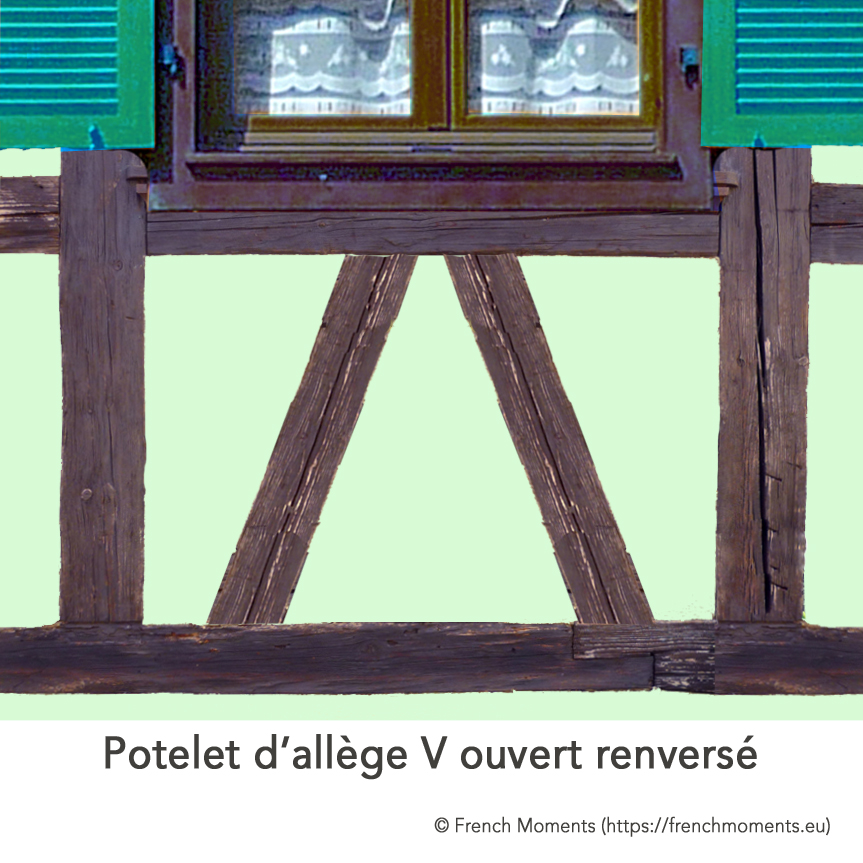

An inverted V

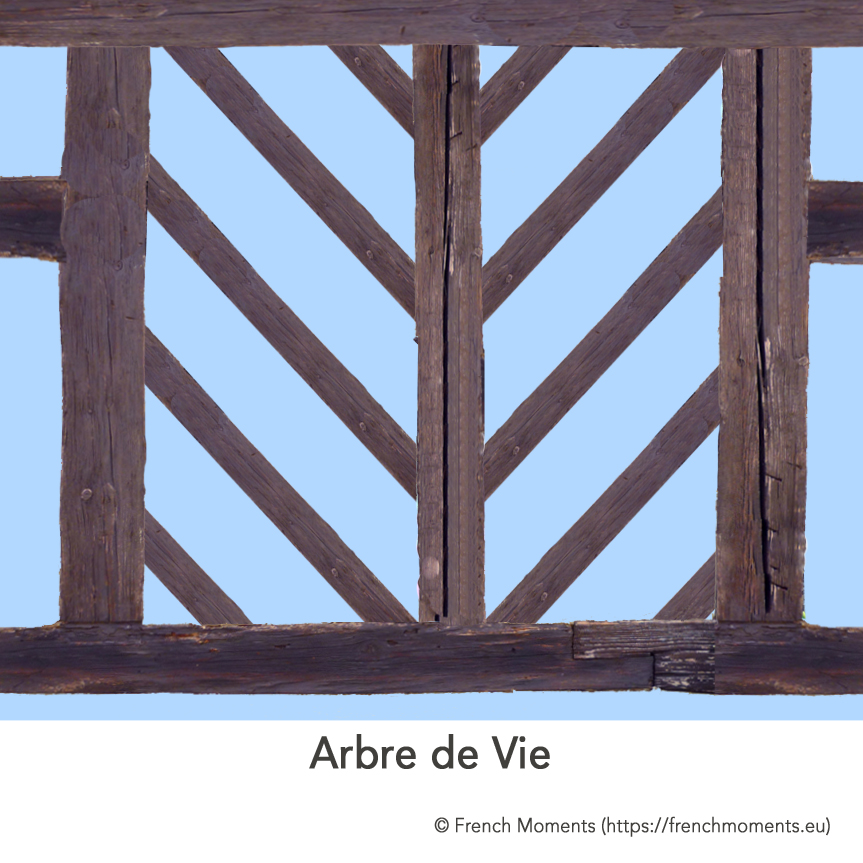

The Tree of Life (Arbre de vie)

Very common in Normandy, the shape is rare in Alsace except in the Sundgau. It symbolises the “source of life”, fecundity, and the knowledge of good and evil as it refers to the tree of life planted in the Garden of Eden.

The Corner Post (poteau cornier)

It is a fundamental element of the framework of a half-timbered house. It is often decorated with various motifs: screw, straight or cable columns and sculpted columns with characters or geometric motives.

The ornamentation can also include fine traditional signposts or richly decorated bow windows, especially in cities and villages surrounded by vineyards.

Houses with a porch can be decorated and adorned with a niche housing a protective statuette.

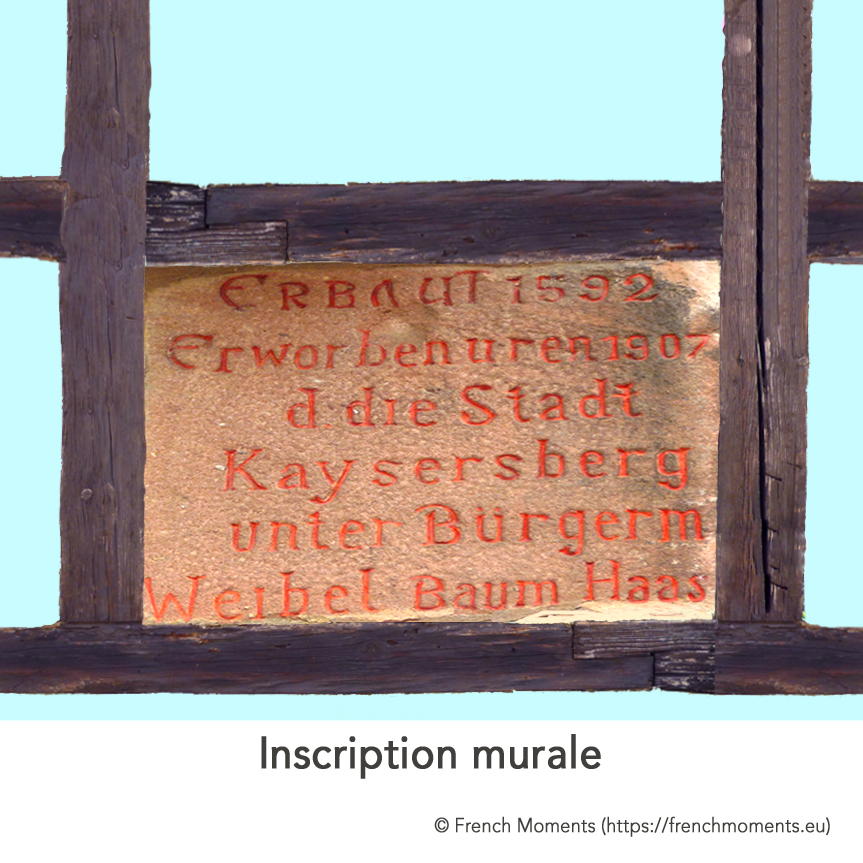

The Alsatian house contains many inscriptions, signs and formulas. For written messages, the language generally used is German, sometimes Latin and rarely French.

Lintels feature the house’s construction year, the owner’s initials and a cartouche featuring the emblems of his profession or corporation.

Very often, cartouches or inscriptions come with a multitude of signs of symbolic character:

The biblical monograms

The IHS is ubiquitous and signifies in Latin “Jesus hominum salvator” and German “Jesus Heiland Seligmacher” (Jesus, Saviour of Mankind). The GMB monogram refers to the Three Wise Men Gaspard, Melchior and Balthazar. Less common is the Christian monogram with a P strikethrough with an X featuring the alpha and omega.

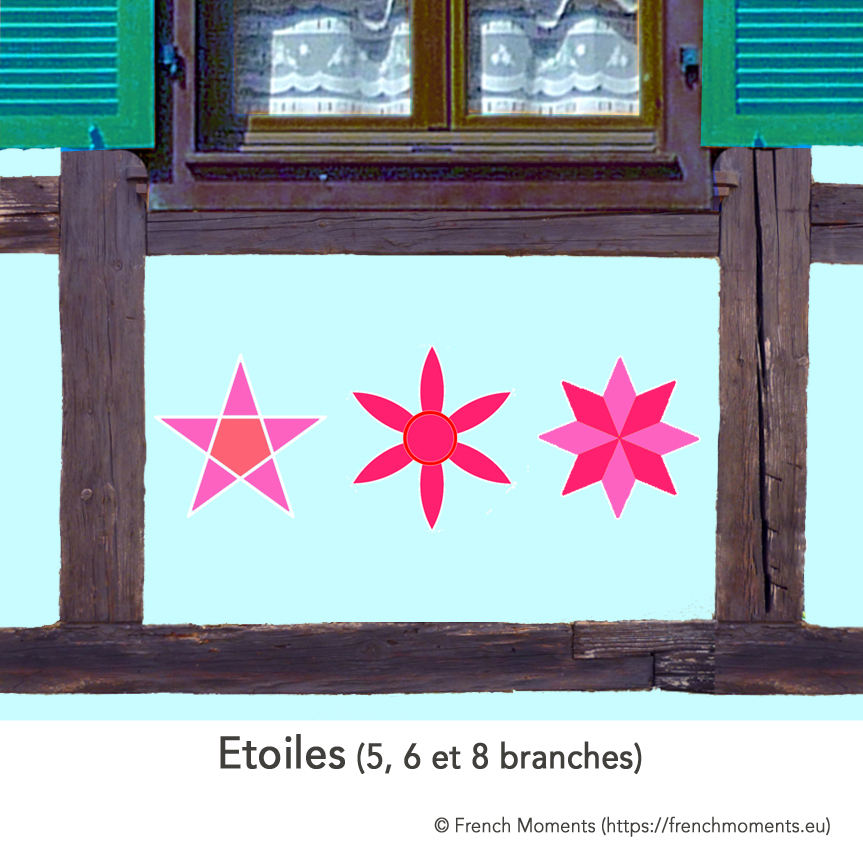

The stars

Very ancient, they are often displayed with four branches (the four cardinal points and the four elements), with five branches (Pentagram which evokes the Mann but also the five elements and the conjuration of curses – (Drudenfüss in Alsatian dialect), with six branches (Hexagram, a sign for plenty but which also refers to the 6 phases of the making of beer), with eight branches (a double of the four branch-star).

The heart

Symbol of passion and love but also fecundity, it is very often displayed in Alsatian houses, especially on shutters. The heart was considered a lucky-charm.

The Lemniscate

(in Alsatian dialect “liegende Acht”, in French “huit couché”) It is the symbol of excellence or infinity, plenitude and longevity.

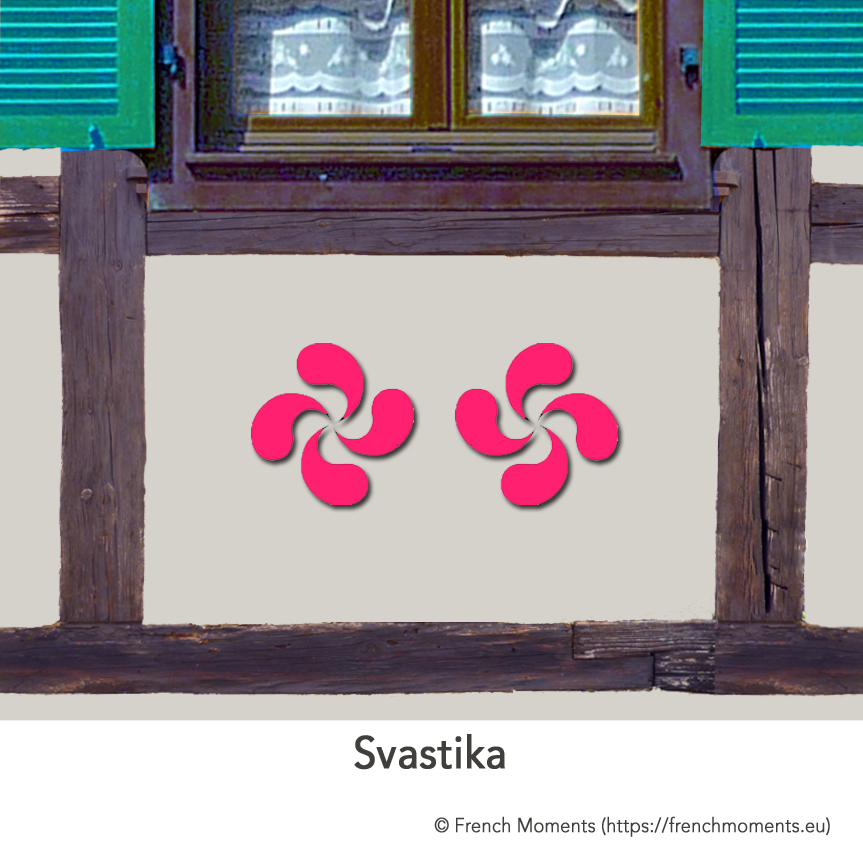

The swastika

The sign symbolises the cycle of the sun, fecundity, but also the risen Christ.

The geranium lipstick for the Alsatian houses

The geranium is arguably the most widespread flower in Alsace. It is found everywhere: on windowsills, balconies, stairs and terraces.

Like a lipstick stroke which emphasises the architecture of the houses, the red flower shows that one’s home is the most beautifully decorated in the street! The tradition of decorating houses with geraniums only dates back to the 18th century. Today, the flower is wrongfully called “geranium”; the plant is a “pelargonium” originating from Southern Africa.