Ahh... the French word "et" and the mysterious French liaison.

It all started with a question from my French student, Janis.

“You said et — and there was no liaison. Is that just for the word et, or for all words ending in -et?”

Excellent question, Janis. And since she is far from the only English speaker to stumble over this — I’ve seen the same puzzled look or heard the same question from many of my French students over the years — here’s the low-down.

1. The Golden Rule: Never stick anything to et

In French, et means “and”.

Simple enough, right? But here’s the thing: you never, ever make a liaison after et.

Not with a vowel. Not with an h muet. Not even if you think it would sound posh.

❌ un homme‿et‿elle → Nope.

✅ un homme et elle → Keep a tiny pause after et.

Why? Because et is like that polite but slightly aloof guest at a party — it’ll stand between two people, introduce them, but it won’t hold hands with either.

2. What about other words ending in -et?

Here’s where learners get confused. In writing, et looks the same in a lot of words:

- navet (turnip)

- poulet (chicken)

- muguet (lily of the valley)

- banquet (banquet)

- billet (note, ticket)

But in French pronunciation, most words ending in -et end with the vowel sound [ɛ].

No liaison is possible from this t, because the sound doesn’t exist in spoken French.

So, the final t is silent. And if it’s silent, you can’t “link” it in a liaison — there’s nothing to link.

Le billet est cher → [lə bijɛ ɛ ʃɛʁ]

The ticket is expensive. No liaison.

Le navet est‿excellent → [lə navɛ ɛt‿ɛksɛlɑ̃]

That [t] you hear? It’s from the verb est, not the turnip.

3. The exception: verbs that actually pronounce the t in liaison

Sometimes, a word ending in -et isn’t a vegetable, a ticket, or a flower. Sometimes it’s a verb:

- il met (he puts)

- elle remet (she puts back)

- il permet (he allows)

Normally, the t is silent if nothing follows. But put a vowel after it, and — voilà — liaison magic:

Il met‿un chapeau → [il mɛ‿t‿œ̃ ʃapo]

Elle remet encore ça → [ɛl ʁəmɛ‿t‿ɑ̃kɔʁ sa]

The t pops up only because of that vowel after it. Without the vowel, it hides again.

4. Famous verbs that do the same trick

It’s not just -et verbs. Any verb ending in a written -t or -d will often pronounce it in liaison:

- il prend‿un café → [il pʁɑ̃‿t‿œ̃ kafe]

- elle vend‿une maison → [ɛl vɑ̃‿t‿yn mɛzɔ̃]

- on attend‿un taxi → [ɔ̃ natɑ̃‿t‿œ̃ taksi]

- est-il là ? → [ɛ‿til la]

5. Beware the et est trap

And here’s where beginners mess up.

You’ve learned that verbs like est make a liaison. But remember: if et (and) comes before it, you’re back to no liaison.

Why? Because et (and) and est (is) may look and sound similar, but they’re different words doing different jobs.

- et = “and” (conjunction, no liaison after it)

- est = “is” (verb, does liaison before a vowel)

Il a pris un taxi et est‿arrivé tôt → [e ɛtaʁive], NOT [et‿ɛtaʁive].

So when you see et est in writing, don’t let the double et/est trick your brain into glueing them together — think of them as two separate little islands.

6. Quick recap for the road (or the café terrace)

- After et → never link. Ever.

- Most -et words → no liaison, because the t is silent.

- Verbs like met → liaison before a vowel, yes.

- Verbs in -t or -d → same rule.

- Don’t over-link — you’ll sound like you’re trying to order wine in a Shakespearean play.

✈️ Traveller tip: Next time you’re ordering in French and your brain screams link everything, remember this rule: et likes its personal space.

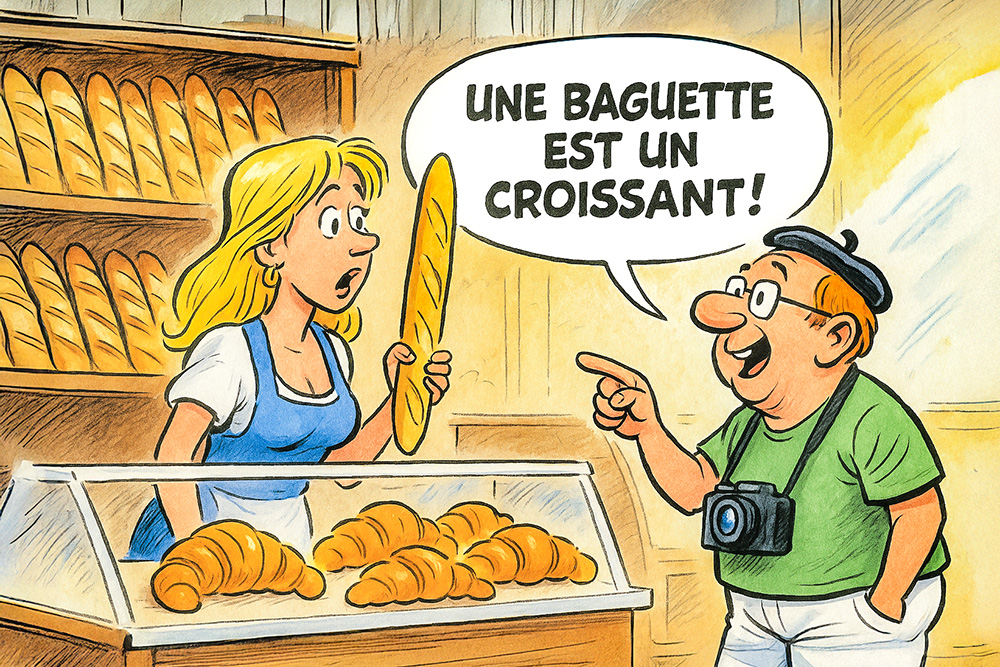

Respect it, and you’ll sound a lot more French than the tourist at the boulangerie proudly ordering une baguette et‿un croissant.

Trouble is, with that cheeky little liaison after et, it sounds like they just declared “a baguette is a croissant”.

Which, as every French baker will tell you, is wildly — and deliciously — wrong. 😅