Nestled in the northeast of France, Belfort is a city rich in history and charm.

For many years, I had the pleasure of knowing this city intimately, thanks to the numerous friends I had there.

Belfort was just 30 kilometres from my home in Alsace, making it a frequent destination for me.

Its intriguing past, from ancient times to its heroic wartime resistance, has always captivated me.

Join me as we delve into the remarkable history of Belfort, uncovering the stories and events that have shaped this unique city.

Where is Belfort located?

Belfort is located at the border of the Rhine and the Rhône basins, in a strategic pass the army named “Trouée de Belfort” (Belfort Gap).

For geographers, the area is called

- Burgundy Gate (Porte de Bourgogne) or

- Alsace Gate (Porte d’Alsace).

It depends on whether one looks to the West or the East.

The Belfort Gap stretches over 30 km between the Vosges and the Jura.

The exact location of the pass lies 14 km East of Belfort, at Valdieu-Lutran, in the Sundgau.

A Germanic-styled old town

This strategic position is evident from the architectural features displayed in the town:

- a Germanic-style old centre and

- a definite French influence in its “faubourgs” or immediate districts.

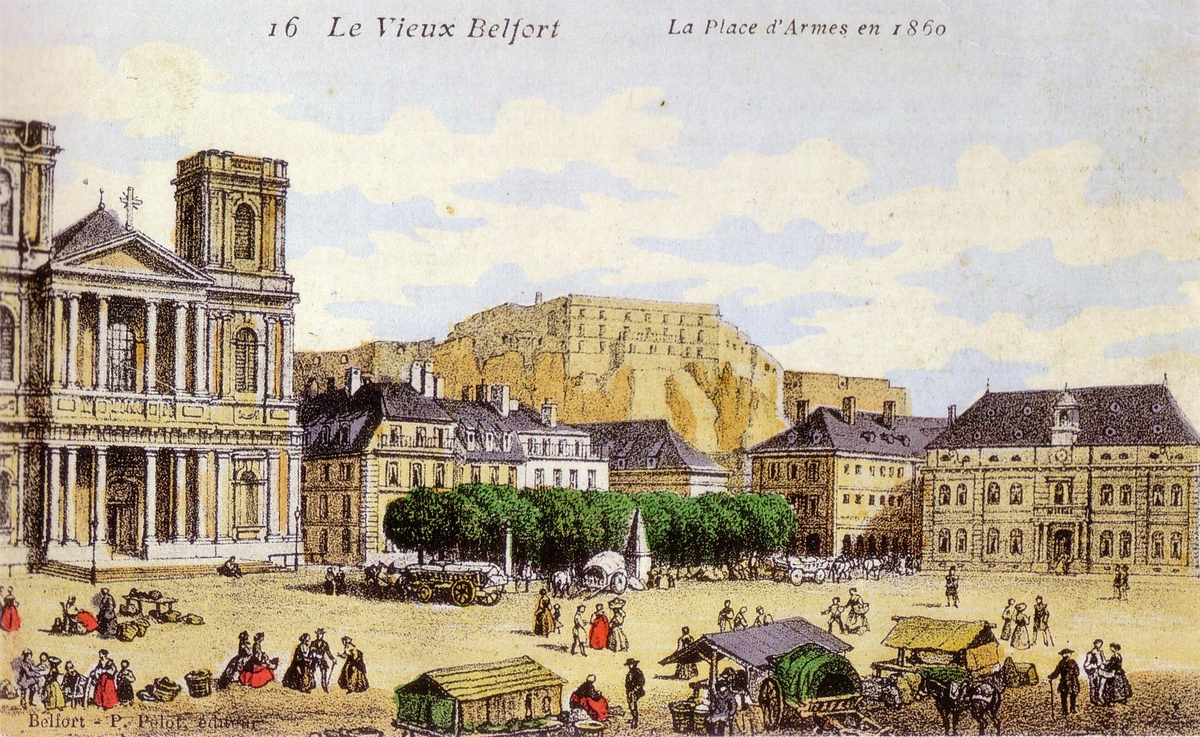

The site of Belfort’s old town is quite impressive from the West.

The town extends from beneath a cliff and stands a monumental stone lion.

At the top of the cliff, a castle (or citadel) still watches over the town.

The Savoureuse, instead of a ravishing name for a river, marks the limits between the old town and the “nouveaux faubourgs”.

The latter are the new districts built between 1871 and 1914 during the rapid demographic growth of Belfort.

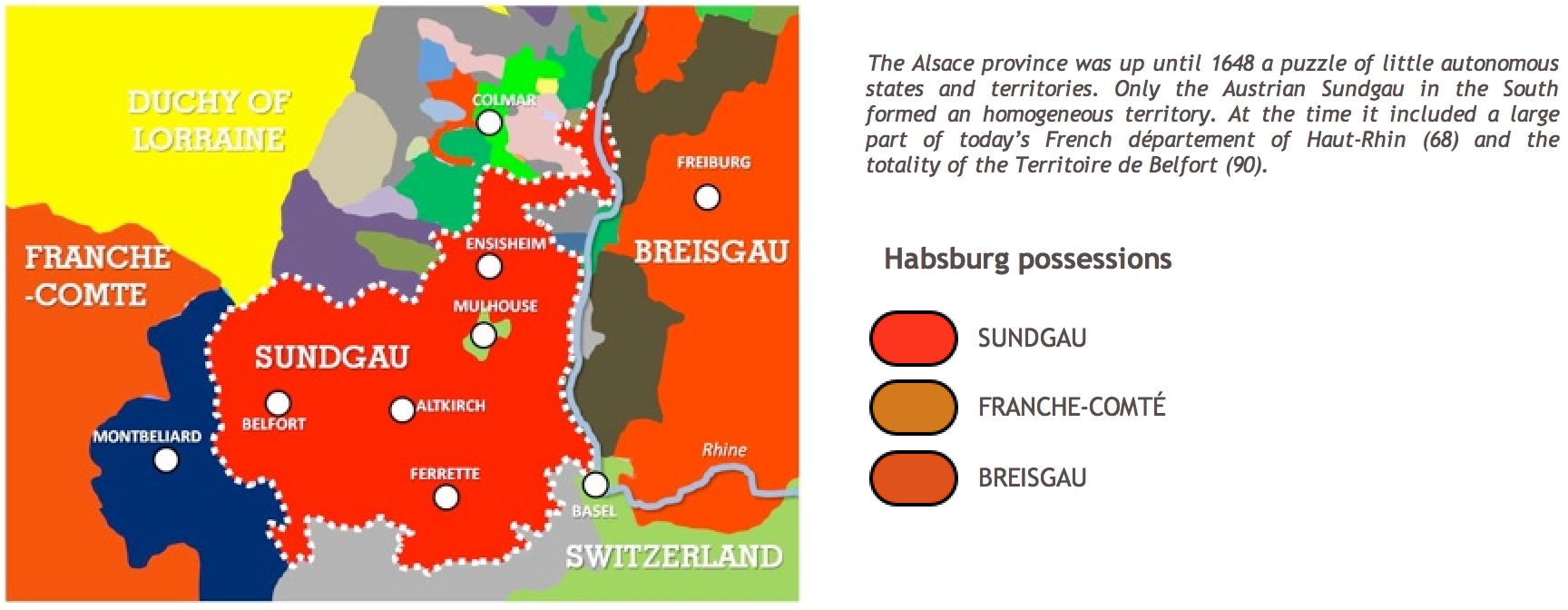

An Austrian Outpost

During most of the Middle Ages, Belfort was an Austrian town.

The Habsburgs possessed it as part of the neighbouring region of Sundgau. In a way, Belfort was an outpost bastion of Austria.

Indeed, it marked the most western post of Vorderösterreich (Anterior Austria) for three centuries, between 1360 and 1648.

The rivalry between the Counts of Montbéliard and Ferrette

In the 12th century, Thierry II, Count of Montbéliard, had a castle built at the top of a steep hill above the Savoureuse River. He named this castle “Belfort”.

Its rival’s territory, Frederic I, Count of Ferrette, extended to the hill, facing the Belfort Castle.

Frederic, in turn, decided to edify his castle, which he named “Montfort”, on the current site of the “Tower of Miotte”.

This ancient tower is very dear to the people of Belfort, who considered themselves “Miottains” – children of the Miotte.

They used to pick up a stone from around the tower to take as a talisman when travelling far away from the city.

The Miotte was destroyed many times, including in 1870-71 and 1940, but it has always been rebuilt.

From this point onwards, the two related families shared a long common history of both happy events and conflicts until the Treaty of Grandvillars.

The Treaty of Grandvillars (1226) first mentioned the name Belfort, presumably referring to its castle, which may have been solid and impressive.

Today, the well and the “Tour des Bourgeois” are the only medieval elements untouched by the successive restorations of the castle.

Belfort: an Austrian bastion

By legal succession, Belfort and its surroundings became an entirely Austrian territory around 1360 until 1648.

Belfort quickly became a Habsburg bastion at the western limits of their growing empire.

By becoming entirely Austrian, the people of Belfort (les Belfortains) were not safe from the attention of Austria’s powerful enemies:

- the influential Duchy of Burgundy,

- the fierce Swiss Confederates and

- the distant kingdom of France.

Due to Belfort’s strategic position between the North and Mediterranean Seas and between the two rivals, Paris and Vienna, the frequent passage of enemy armies did more harm than good.

In 1365, the Holy Roman Empire – emperors from the Habsburg dynasty – decided to base 400 soldiers in Belfort.

A catholic stronghold

Later, in the 16th century, Belfort found itself surrounded by influential Protestant cities:

- Mulhouse and Basel to the East,

- and Montbéliard to the South.

The Habsburgs took an unyielding stance against all attempts to introduce the Reformation in Belfort and the Sundgau.

Subsequently, the dynasty spearheaded the Counter-Reformation, encouraging the introduction of anti-reformist works (particularly monasteries and Jewish schools) in the region.

However, Protestantism continued progressing in Europe after the Peace of Augsburg in 1555.

The Protestant princes of Bohemia refused to recognise the authority of the Holy Roman Empire (HRE) emperor, Ferdinand II (who himself was a Habsburg).

War erupted in 1618 due to the extreme tension between Catholics and Protestants and the emperor and Protestant princes.

Belfort becomes French

France’s intervention further complicated the political situation, as France had long been hostile to the House of Austria’s ambitions in Europe.

During the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), each side coveted Belfort, which was thus considered a sort of strategic “Gibraltar of the East.”

The troubled years of the 1630s

In 1632, the Swedish army besieged Belfort. The city surrendered in January 1633.

Different warmongers took and retook the town, which suffered devastation for the next three years.

On the 28th of June 1636, the French definitively took the city. Fighting in the name of the King of France, Louis de Champagne, Count of Suze, seized the fortified town in the middle of the night in an incredible act of boldness.

The Count of Suze’s motto was famous for its brief but tenacious message: “Never surrender!” (Ne capitulez jamais).

The King of France’s victories forced the Habsburgs to surrender Upper Alsace to him.

The Habsburgs withdrew from the other side of the Rhine and made Freiburg im Breisgau the new capital of the rest of their possessions in Anterior Austria.

On the 24th of October 1648, the Habsburgs signed the Treaty of Westphalia, which stipulated the transfer of Belfort and the Sundgau to France.

From the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) to 1789

From 1648, the King of France, Louis XIV, ruled over Belfort.

In 1679, the military engineer Vauban visited the town and designed plans for new fortifications.

You can still see his work when driving around Belfort, particularly from the viewing platform of the castle.

The Gate of Breisach

The fortifications designed by Vauban included two gates, the Breisach Gate and the France Gate (destroyed in 1892).

Each gate was protected by a demi-lune (or ravelin), a triangular fortification in front of the inner works of the Belfort fortress.

The Breisach Gate’s ravelin is linked to the bastion by a bridge spanning the trenches.

More than just a military construction, the Breisach Gate of Belfort was designed to bring glory to the King of France, Louis XIV.

![Fortified City Gates of Alsace - Porte de Brisach, Belfort © Andrzej Harassek - licence [CC BY-SA 3.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Belfort-Porte-de-Brisach-©-Andrzej-Harassek-licence-CC-BY-SA-3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

Several ornamental embellishments still testify to this endeavour: fleurs-de-lis surmounted by the royal crown and engraved in the pediment, the sun (emblem of King Louis XIV, the Sun King) and his Latin motto “Nec pluribus impar” (none can be compared to him).

Notice the date – 1687 – engraved in Roman numerals under the pediment.

The Gate of Breisach (Porte de Brisach), built in 1687, is particularly impressive and worth a visit.

![Fortified City Gates of Alsace - Porte de Brisach, Belfort © Krzysztof Golik - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Belfort-Porte-de-Brisach-©-Krzysztof-Golik-licence-CC-BY-SA-4.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

To appreciate the appeal of Vauban, a ride along the Avenue du Capitaine de la Laurencie reveals the impressive set of ramparts built by Vauban, as the street was traced in between the walls.

The Saint-Christophe church

In the old town, the Cathedral Saint-Christophe was built in pink sandstone from the Vosges between 1727 and 1750 in a classical style by Henri Schuller from the designs of Jacques Mareschal.

The wrought-iron railings inside the church encircle the choir stalls and are covered in gold leaves. Those of Place Stanislas influenced them in Nancy.

The magnificent organ, listed as a historic monument, dates back to 1752 and is from Joseph Valtrin.

Initially an abbatial church, the building only became a cathedral in 1979, when the bishopric of Belfort-Montbéliard was created.

The old town

Until the end of the 19th century, the old town of Belfort was surrounded by fortifications designed by Vauban.

The old town is relatively small but has been restored, making it an enjoyable stroll, particularly in summer.

From the castle’s cliff to the banks of the Savoureuse River, the old town alternates between picturesque streets, small lanes and squares.

The steep roofs of the old town are best viewed from the terrace of the castle and, at a simple glance, share similarities with houses of neighbouring towns of Delle, Altkirch, Ferrette or even Porrentruy (Switzerland).

Belfort from the French Revolution to 1870

During the French Revolution (1789), the Province of Alsace, where Belfort belonged, was administratively restructured.

From December 1789 to February 1790, the Constituante completely reorganised the French administration.

The former provinces (Lorraine, Normandy, Alsace, Burgundy, etc.) gave way to départements, which were divided into several districts (or arrondissements).

Thus, the province of Alsace was divided into two départements: the Bas-Rhin to the north and the Haut-Rhin to the south, with their respective administrative centres of Strasbourg and Colmar. Belfort, Mulhouse, and Altkirch became the three sub-prefectures of the Haut-Rhin.

The Haxo fortifications

Under the Bourbon Restoration and the July Monarchy, General Haxo commissioned the modernisation of Belfort’s fortification system, transforming the place into a genuinely entrenched camp defended by the castle itself and two new bastions: the Miotte and the Justice.

All these military forts were connected and linked to the Castle.

Haxo also modernised the castle’s fortifications by digging two ditches and building two new lines of walls.

At the entrance to the castle is a small cour d’honneur bordered by the Haxo castmates, which have since been transformed into exhibition halls and cafés.

One of them, a well dating back to the medieval castle, is 67 metres deep.

The great design by Haxo can be seen at its best from the castle’s panoramic terrace.

From there, the view extends from the Jura Mountains to the hills of Salbert and the Hautes-Vosges (Ballon de Servance, Ballon d’Alsace, Baerenkopf, and Rossberg).

Visit the citadel

Since July 2007, a section of the citadel, along the moats and the big underpass, has been open to the public.

The trail includes a spectacular sound and light show in the great underground grotto, which has been redesigned for it.

This original journey is “La Citadelle de la Liberté” (Citadel of Liberty).

The citadel houses the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire (Museum of Arts and History), which displays paintings of Dürer and Doré alongside other local artefacts and exhibits on the town’s former military heroes.

The Siege of Belfort (1870-71)

1871 was a year that would go down in Belfort’s history. Indeed it symbolises the defeat of the French army by the Prussians. And – most importantly – Belfort’s memorable resistance, which lasted 103 days.

In November 1870, the Prussian army (40,000 soldiers) started to besiege Belfort and occupied all its surrounding villages.

For 73 consecutive days, 3,500 French soldiers and over 14,000 inexperienced local fighters endured Prussian bombing during winter.

The Prussian enemy set up 200 big guns that fired more than 5,000 shells daily.

On February 13, 1871, 21 days after the armistice between the French and the Prussians was signed in Versailles, the French Government ordered Colonel Denfert-Rochereau, the commander of the French army, to capitulate.

In doing this, French Head of State Adolphe Thiers hoped to keep Bismarck from annexing Belfort.

The Prussian statesman had wanted to bring the whole of Alsace—including Belfort—into the new German Empire.

The Belfort resistance echoed all around France. It exemplified French courage and honour. Unlike Paris, the Prussian army never took Belfort in military action.

Only the French government ordered its capitulation while the Reich Empire was proclaimed in the Palace of Versailles.

The Lion of Belfort

Auguste Bartholdi designed a monumental statue to symbolise the heroic siege.

You will find it below the castle: this is the Lion of Belfort.

Belfort is separated from Alsace

If Belfort were historically part of Alsace, most of the local population would tell you that calling their beloved city “Alsatian” is nonsense.

Since 1871, the ‘Cité du Lion’ has been separated from the département of Haut-Rhin.

Only a few would know of the pre-Franco-Prussian war territorial division.

Furthermore, the town has always been French-speaking, even during the long era when the city was Austrian.

This did not particularly bother the Habsburgs, as it was strategically placed in the Burgundy Gate.

Why the town is not part of Alsace anymore?

The French were obliged to surrender the territories with German culture and language (north-east Lorraine and Alsace) to the victors.

However, they somehow managed to keep Belfort and its immediate surroundings.

The preliminaries of the French-Prussian Treaty (Treaty of Frankfurt), signed on the 26th of February 1871, set the new border west of the Haut-Rhin département.

Therefore, Article 1 stipulated that:

“On the other hand, the town of Belfort and its fortifications will remain French with a radius which will be determined later…”

A difficult negotiation

Thiers and Bismarck had difficulty negotiating the drawing up of the Frankfurt Treaty.

Letting the heroic city of Belfort become Prussian hurt the French patriotism of many Republicans.

The Prussian state officers were pleased with France’s proposal to exchange twelve iron-rich Lorraine villages for Belfort and 105 communes of the Haut-Rhin.

As soon as it was announced, the Prussians accepted the idea, which the French National Assembly confirmed later.

Metz and the département of Moselle were thus given to the Prussians in exchange for Belfort and its Alsatian-part district.

The detached part of the Haut-Rhin, which remained French, was not immediately called “Territoire de Belfort” (Belfort Territory) but rather “French District of the Haut-Rhin”.

It was only in 1922 that the Belfort Territory—“the temporary entity waiting for the return of the Haut-Rhin to France”—became an official département.

Despite the Haut-Rhin being returned to republican France in 1918, the French authorities were not keen on returning the territory to the département as constituted in 1789.

From then on, Belfort and its environment were no longer considered part of Alsace.

During the Belle Époque

Until the Franco-Prussian war, the demographic growth of the town increased only slightly, despite the arrival of railways in 1858.

A demographic boom

However, after the war, Belfort’s population dramatically rose from 8,030 to over 40,000 from 1870 to 1914.

In the same way as Nancy in Lorraine, Belfort welcomed a flow of Alsatians who opted to keep their French nationalities, thus compelling them to immigrate outside Alsace.

Many industrialists from nearby Mulhouse or Colmar choose to live in Belfort.

They contributed to its growth and influence in the region.

The wealthy newcomers were bringing capital which was used to create new companies.

A famous example is that of the SACM (Société Alsacienne de Constructions Mécaniques).

Initially based in Mulhouse, it moved to Belfort in the 1870s.

Today, the SACM is known as “Alstom”, famous for its TGV trains, some of the fastest in the world.

The city grew outside the limits of Vauban’s fortifications.

It spread across the other side of the Savoureuse River.

Unlike its neighbour Mulhouse, buildings from the Belle Époque, such as Haussmann architecture, resemble those built in Paris, thus contrasting with the more Germanic style of the old town.

More info about the ‘Cité du Lion’

Explore Comfortable Accommodations in Belfort

Planning a visit to Belfort? You’ll find a range of comfortable and charming accommodations to suit your needs.

From cosy boutique hotels to modern apartments, there’s something for everyone.

Whether you want to stay in the heart of the city or prefer a quiet retreat, Belfort has it all.

Ready to book your stay? Check out the best options available on Booking.com and find the perfect place to rest after exploring this historic city. Browse the map below:

How to get there

- Belfort is easily accessible by car from Alsace’s main cities, Strasbourg, Colmar, and Mulhouse, as well as from Montbéliard and Besançon in Franche-Comté.

- If you travel from Australia, New Zealand, or America, you could fly to Paris Charles de Gaulle, Zurich, or Frankfurt Airports and rent a car there. The nearest airport is the Euroairport near Basel.

- The TGV Rhin-Rhône from Paris-Gare de Lyon takes 2.15 hours to the new Belfort-Montbéliard-TGV railway station.

Useful Links

- Our article about the Lion of Belfort

- The Lion’s replica in Place Denfert-Rochereau in Paris

- The History of the Sundgau

- Read more about the Lion of Belfort on our French blog!

- The official website of the Tourist Board of Belfort.

Pin it for later

Like this post about this historic city in northeastern France? Pin it for later!

Well, Pierre,

I came across this article of yours by chance and I must say, it does picture my native town in all its physical & cultural dimensions very nicely indeed!

Thank you

Bertrand

Thank you Bertrand for your comment… I’m delighted to hear you liked it! There’s so much to say about Belfort it’s always a pleasure to promote this lovely town. A bientôt ! 🙂

Thank you so much Pierre. You made our visit to Belfort much more rewarding knowing the history and advice on places to visit.

You’re welcome! 🙂