Henri IV may have been one of France’s most popular kings, but Paris hides his darkest secret in plain sight.

Take the Rue de la Ferronnerie, for instance.

Today it’s a narrow, noisy little street not far from Les Halles, lined with shopfronts, buzzing scooters, and impatient pedestrians.

Nothing about it screams “royal drama”.

And yet, right here, on a spring afternoon in 1610, the King of France was stabbed to death.

Yes, a king. Not a duke, not a minor noble, but Henri IV himself—the so-called Good King Henry, the Vert Galant, the man who promised a chicken in every pot.

Try to picture it: you’re weaving your way through the crowd, baguette under your arm, and suddenly realise you’re walking on the exact spot where France’s history bled onto the cobblestones.

That’s the thing with Paris—every corner has a story. Some involve croissants, others involve conspiracy, daggers, and a dead monarch.

Who was Henri IV, the “Vert Galant” King?

Before we dive into the blood and daggers, let’s meet our doomed protagonist.

Henri IV wasn’t just any king—he was the first of the Bourbon dynasty, the man who pulled France out of three decades of religious wars, and the one every French schoolchild still knows as le Bon Roi Henri.

He was born in Pau, down in the Pyrenees, with Béarnais grit in his veins.

Baptised Catholic, raised Protestant, and switching sides more often than some people change their Netflix subscription—six times, to be exact—Henri was nothing if not adaptable.

Pragmatism was his trademark.

In fact, when asked why he finally converted back to Catholicism to secure the crown, he supposedly shrugged: “Paris is well worth a Mass.”

You have to admit, it’s a line worthy of a PR genius.

But Henri wasn’t all politics.

He had a softer (and slightly scandalous) side too.

Known as the Vert Galant—which loosely translates to “the Green Gallant”, or in modern terms, “an energetic ladies’ man”—he juggled mistresses, fathered more than 20 illegitimate children, and still found time to launch construction projects like the Pont Neuf, the Place des Vosges and Place Dauphine.

Imagine trying to balance Tinder, nation-building, and the occasional religious war—that was Henri’s life in a nutshell.

Yet, for all his charm and his vision, Henri IV was never fully accepted.

- To the Catholic ultras, he was still the heretic who once led Protestant armies.

- To some Protestants, he was the sell-out who’d abandoned their cause.

- And to his rivals abroad, he was the unpredictable king who might upset Europe’s fragile balance of power.

In short: loved, hated, and always in danger.

Henri IV: A King under Threat

Being King of France in the early 1600s was a bit like being the lead actor in a Shakespearean tragedy—you never knew which side character might suddenly stab you in Act III.

Henri IV knew this all too well.

From the day he took the throne in 1589, knives seemed to follow him.

He dodged more than twenty assassination attempts during his reign—an achievement worthy of its own Guinness World Record.

Some tried with daggers, others with crossbows, even one reckless soul with an arbalest in Meaux.

One student, Jean Châtel, managed to slash Henri’s lip in 1594, breaking a tooth in the process.

Not quite regicide, more like very aggressive dentistry.

Why so many attempts?

Because Henri was a king whom nobody fully trusted.

To the Catholic League, his Protestant past never washed away.

To Protestants, his conversion to Catholicism looked like betrayal.

To Spain and the Holy Roman Empire, he was the wildcard who might ally with Protestant princes against them.

Add to this a Europe simmering with succession disputes—like the crisis over the duchy of Juliers in 1609—and Henri looked like the spark that could ignite a continental bonfire.

And yet, after surviving all these threats, Henri grew almost cavalier about danger.

He liked to ride through Paris with little protection, waving and joking with the crowds as if to say, “See? No one would dare touch me.”

In a way, he was right.

Until the one man who did dare was waiting with a knife, in a narrow street where the king’s carriage had nowhere to go.

14 May 1610: A Paris Backstreet Turns Red

Picture the scene. It’s a warm spring afternoon in Paris, 14 May 1610.

Henri IV is in his carriage, bouncing along the cobbled streets with a few nobles squeezed in beside him.

He’s on his way to visit his trusty minister, the Duke of Sully, who’s stuck in bed with the flu.

The king, ever the extrovert, decides to leave the leather curtains of his carriage rolled up—why hide from the people when you can nod and smile your way through the city?

Bad idea.

The carriage turns into the Rue de la Ferronnerie, a cramped lane barely four metres wide, hemmed in by houses, shops, and hawkers.

And then, fate intervenes.

Two carts—one laden with hay, the other with barrels of wine—jam the street.

The royal coach grinds to a halt, right outside an inn with the ominous name Au cœur couronné transpercé d’une flèche (“The Crowned Heart Pierced by an Arrow”).

You couldn’t invent better foreshadowing if you tried.

Enters Ravaillac

From the crowd, a man steps forward.

François Ravaillac, a failed clerk turned religious fanatic, has been stalking the king for days.

He’s convinced God wants him to stop Henri from launching a war against Catholic Spain.

He clambers onto a wheel spoke, leans in through the open carriage, and plunges his knife into the king’s chest.

Once, twice, three times.

The first blow grazes Henri.

The second tears through his lung and slices his aorta.

The king collapses instantly, blood soaking his doublet.

The third stab glances off a duke trying to shield him.

Within minutes, Henri IV—the peacemaker, the lover, the builder of Paris—is dead.

Henri IV Assassinated: Panic erupts

Some shout that it was a conspiracy.

Others try to lynch Ravaillac on the spot, but he stands calmly, bloodied knife still in hand, as if waiting for divine applause.

Instead, the crowd roars with fury.

He is dragged away before they can tear him apart.

The street, once just another noisy Parisian alley, has become a stage for regicide.

Even today, if you walk Rue de la Ferronnerie and pause at the discreet plaque set into the pavement, you can almost hear the echo: the jostling carts, the startled cries, the thud of a body falling in the carriage.

History doesn’t get more visceral than this.

Ravaillac: Fanatic or Pawn?

François Ravaillac was not the kind of assassin you’d cast in a Hollywood thriller.

No cloak-and-dagger nobleman, no sleek mercenary.

He was a failed schoolmaster, a religious obsessive, and a man plagued by visions.

Hardly James Bond. Yet somehow, he succeeded where twenty others had failed.

The authorities, naturally, wanted answers.

Who sent him? Spain? The Pope? The Queen herself? A shadowy cabal of disgruntled nobles?

Paris was buzzing with conspiracy theories before Henri’s body was even cold.

The official verdict, though, was disappointing: Ravaillac had acted alone, a lone fanatic with a knife and a divine mission.

If his crime was swift, his punishment was anything but.

Ravaillac was tortured, questioned, and tortured again—though no accomplices ever emerged.

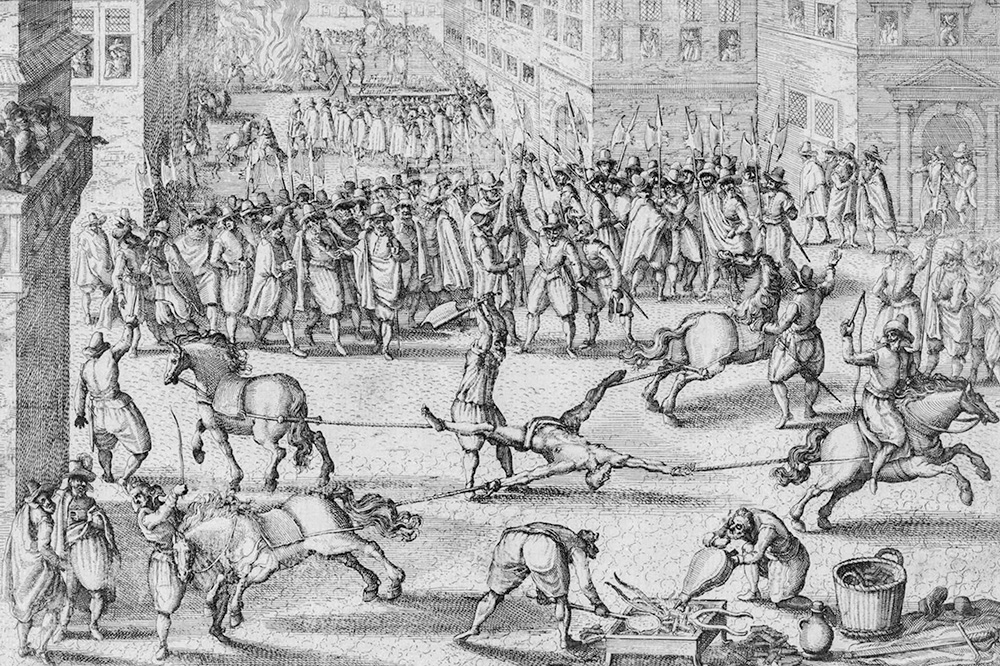

Then came his execution, staged in front of Notre Dame and finally on the Place de Grève.

To call it gruesome is an understatement.

His flesh was torn with red-hot pincers, molten lead and boiling oil were poured into the wounds, his right hand (the stabbing hand) was burned with sulphur, and at the end, his body was torn apart by four horses.

The crowd, unsatisfied, scattered what remained.

A brutal death for a brutal act.

And yet, amid the horror, one detail stands out: Ravaillac apparently expected to be celebrated.

He thought the people would hail him as a new Jacques Clément, the monk who’d killed Henri III.

Instead, they cursed him so violently that even he seemed bewildered.

“I was told this deed would please the people,” he supposedly murmured, realising far too late that history wasn’t going to crown him a hero.

Was he really alone? Or was he, as some still whisper, a pawn in a bigger game of dynastic intrigue?

More than four centuries later, we still don’t have a definitive answer.

What we do have is the chilling certainty that a single knife in a Paris backstreet changed the course of French history.

The Aftermath: A Kingdom in Shock

France reeled. The king who had promised peace after decades of religious wars lay dead, and his heir—Louis XIII—was not yet nine years old.

The country braced itself for chaos.

First came the funerals, and if you think modern state ceremonies are theatrical, you should have seen 1610.

Henri’s embalmed body was laid out at the Louvre beneath gold-draped canopies, while priests said hundreds of Masses every day.

Beside him, a wax effigy dressed in coronation robes sat on a throne, complete with crown and sceptre.

Twice a day, servants brought this wax king elaborate meals, as though he might sit up and tuck in.

A bizarre medieval tradition, but one that symbolised continuity: even in death, the king still reigned.

Meanwhile, the real Henri’s heart was placed in an urn of silver and dispatched to the Jesuit college of La Flèche, fulfilling one of his wishes.

By late June, the coffin travelled to Saint-Denis, the resting place of French monarchs.

On July 1st, Henri IV—once so alive, so defiant—was lowered into the crypt.

Over it all loomed Marie de Médicis, his Italian-born queen, now regent.

She was crowned at Saint-Denis just the day before Henri’s death, as if fate had been preparing her.

Surrounded by favourites like the Duke of Épernon and the scheming Concini, she steered France away from her husband’s anti-Spanish policies and into a more conciliatory stance with Catholic powers.

The Edict of Nantes still stood, but the delicate balance Henri had fought for began to tilt.

Yet out of the trauma emerged something new: the idea that the king’s person was sacred.

Two monarchs in a row had now been assassinated—Henri III and Henri IV.

The lesson was clear: a strike at the king was a strike at France itself.

The monarchy hardened, wrapping itself in the armour of absolutism.

By the time Louis XIII and later Louis XIV ruled, the king would be untouchable—literally, politically, and ideologically.

Henri IV the Legend

If Henri IV’s life ended in a bloody Paris backstreet, his afterlife blossomed into myth.

Dead kings don’t usually get good PR, but Henri became an exception.

Almost immediately, tributes poured in—sermons, tragedies, even whole epics.

Writers cast him as the golden monarch France had lost too soon.

By the eighteenth century, the legend of le bon roi Henri was in full bloom: a jovial, tolerant, almost philosophical king who loved his people, drank good wine, and dreamed of every family having a chicken in their Sunday pot.

Never mind that his tax policies weren’t always so kind—posterity likes its heroes uncomplicated.

Artists joined in too.

Rubens painted him ascending like a Roman god.

Voltaire wrote an epic poem, La Henriade, to glorify his reign.

Playwrights, painters, poets—everyone wanted a piece of the king who’d died too soon.

Even a popular drinking song, Vive Henri IV!, turned him into the people’s monarch.

Henri IV: A useful nostalgia

But the legend wasn’t just nostalgia—it was useful.

During the Fronde, rebels invoked Henri’s memory as the “good king” in contrast to his successors.

Under Louis XV, he was recast as a model of benevolent monarchy.

During the Revolution, Henri’s tomb was desecrated along with the others, yet his embalmed body was so well preserved that it was propped upright for gawkers to view.

Creepy? Absolutely. But it also proved how enduring his presence was.

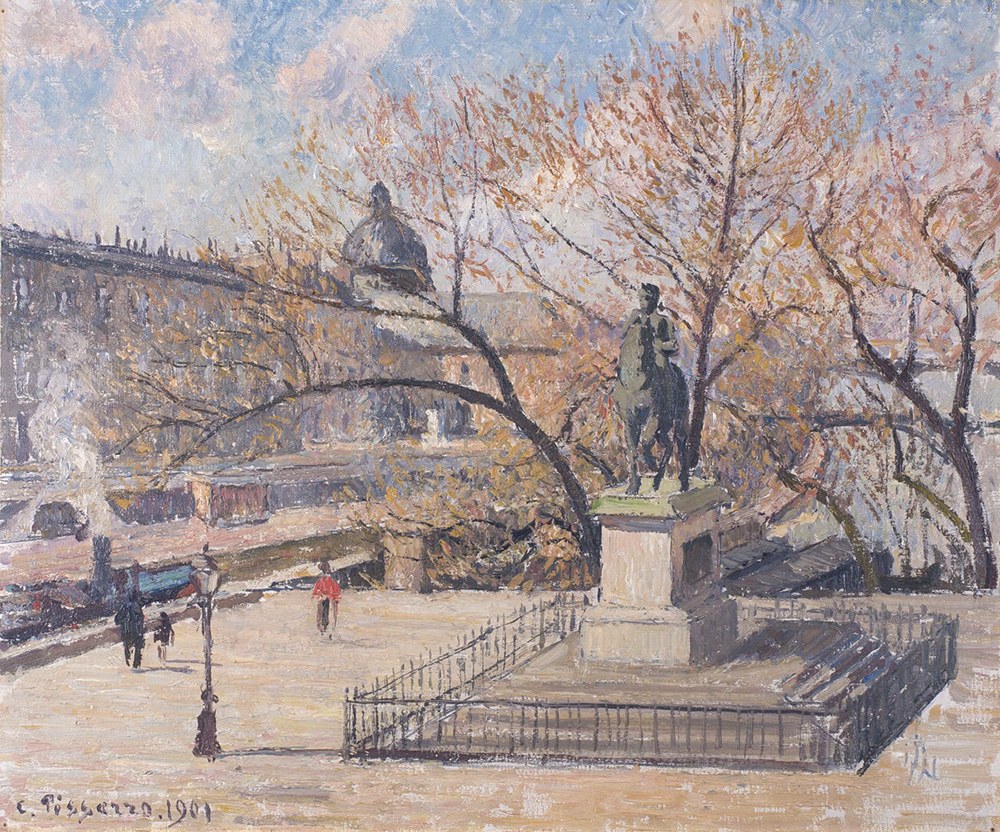

In 1818, a new statue of him went up on the Pont Neuf, cast from the bronze of Napoleon’s toppled column.

That says it all: France needed a unifying symbol, and Henri, the once-controversial, womanising, multi-faith king, was rebranded as a national father figure.

He became a kind of historical comfort food.

Walk through the Castle of Pau today and you’ll still find his legendary turtle-shell cradle.

![Castle of Pau © Sylvain NGR - licence [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Castle-of-Pau-©-Sylvain-NGR-licence-CC-BY-SA-4.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

In popular memory, he’s the king who laughed, loved, and left Paris grander than he found it.

The fact that he had over 20 illegitimate children and once switched religion six times?

Details, mere details.

Conclusion: Rue de la Ferronnerie

And so we circle back to Rue de la Ferronnerie.

Tucked into the bustling 1st arrondissement of Paris, in the heart of the old Les Halles district, the Rue de la Ferronnerie is one of those streets that carries centuries of history in its stones.

Once called the “rue des Charrons” for the wheelwrights who lived there, it changed its name in the 13th century when Saint Louis allowed ironmongers (ferronniers) to set up their stalls along the cemetery of the Innocents.

Narrow and cramped—barely four metres wide in Henri IV’s day—it was here, in front of what is now number 11, that the king was fatally stabbed in 1610.

Today, the street stretches between Rue Saint-Denis and Rue de la Lingerie, accessible from the Châtelet–Les Halles hub, but back then it was a claustrophobic bottleneck, perfect for an assassin’s ambush.

Over time, the street was widened under Louis XIV, its houses rebuilt, but the name Ferronnerie still lingers, echoing the clang of medieval ironmongers’ trade.

Most people rush along without a second glance, without knowing it was the stage of royal tragedy.

But there it is: a modest plaque set into the pavement, marking the spot where Henri IV’s heart beat its last.

![Rue de la Ferronnerie - Commemorative Plaque © Gilles390 - licence [CC BY-SA 3.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Rue-de-la-Ferronnerie-Plaque-©-Gilles390-licence-CC-BY-SA-3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

Standing there, I found myself torn between two moods.

On the one hand, it’s chilling—this very place once echoed with the king’s dying gasp, the panicked cries of dukes, the stamp of horses and carts frozen in traffic.

On the other, it’s oddly comic: the most powerful man in France was brought down not in battle, but in a traffic jam caused by hay and wine.

Paris, in its eternal theatricality, delivered perfect tragic irony.

Henri IV became le bon roi Henri, remembered for tolerance, laughter, and dreams of Sunday chicken (Poule au pot).

But here, on this cramped stretch of cobblestone, we see the darker truth: kings bleed, kingdoms wobble, and history can pivot on a blade.

Next time you stroll through Paris, pause before the plaque.

Forget the rush, the noise, the kebab smells, and listen.

If you have an ear for echoes, you may just hear the rustle of a carriage curtain, the hiss of steel, and the last breath of the king who once declared Paris was worth a Mass.

Because in Paris, history doesn’t hide—it waits.

Sometimes, right under your feet.